This is the first part of the latest in a series of blog posts looking at the some of the problems behind the way that we access family history sources via the major commercial websites.

In previous posts I’ve looked at the dangers inherent in blindly following hints; I’ve considered the question of how complete the various countywide parish register collections are; I’ve asked why the commercial websites seem to be incapable of correctly describing the documents in their databases; and I’ve examined Ancestry’s apparent unwillingness to distinguish between user submitted content and original source material.

Now I want to consider another area of concern by taking a close look at a couple of databases (one on Findmypast (FMP) and one on Ancestry – I always like to be fair in these matters!) where the commercial websites involved in the digitisation of a particular set of records have done a particularly bad job of it all. Also, in both cases the databases include some significant data which is just wrong…

We’ll start with Findmypast’s Index To Death Duty Registers 1796-1903.

The Death Duty registers and related documents are an exceptionally useful set of records (they would have been even more useful but for the actions of Lord Denning!). They record the payments of a series of taxes (Legacy Duty, Succession Duty and Estate Duty) payable on the estates of people who died while domiciled in England and Wales between 1796 and 1903. The registers were created and maintained by clerks at the Stamp Office (later the Inland Revenue) using details submitted to them by clerks at the various probate courts. Before 1812 the probate courts sent an abstract of the details on a pre-printed form: after that, copies of the original wills or grants of letters of administration were sent to the Stamp Office.

They are undoubtedly a complex set of records and prior to the Findmypast digitisation, access to them was severely restricted: essentially, you had to be able to make a visit to the National Archives (TNA) at Kew, where you could view the registers, along with their associated finding aids, either on microfilm (pre-1858) or as original documents.

The agreement between TNA and FMP was to digitise the contemporaneous indexes (properly known as ‘alphabets’) rather than the registers themselves: a disappointing, although understandable decision, as the alphabets had already been microfilmed while nearly half of the registers remain unfilmed.

The format of the alphabets changed over the 108 years during which the register system was in place. The following details were recorded:

This is, by necessity, somewhat over-simplified – the headings, for example, changed over the years and the terms ‘testator’ and ‘executor’ were substituted by ‘intestate’ and ‘administrator’ in the case of letters of administration.

Findmypast’s Index To Death Duty Registers 1796-1903 offers the following searchable fields:

- First name(s)

- Surname

- Year

- County

- Court

The always-useful ‘Optional keywords’ field is also available.

Search results are returned under the five headings/fields listed above with the addition of the ‘Residence’. The transcription also includes the TNA reference to the document. In essence, this seems like a fairly reasonable approach. However…

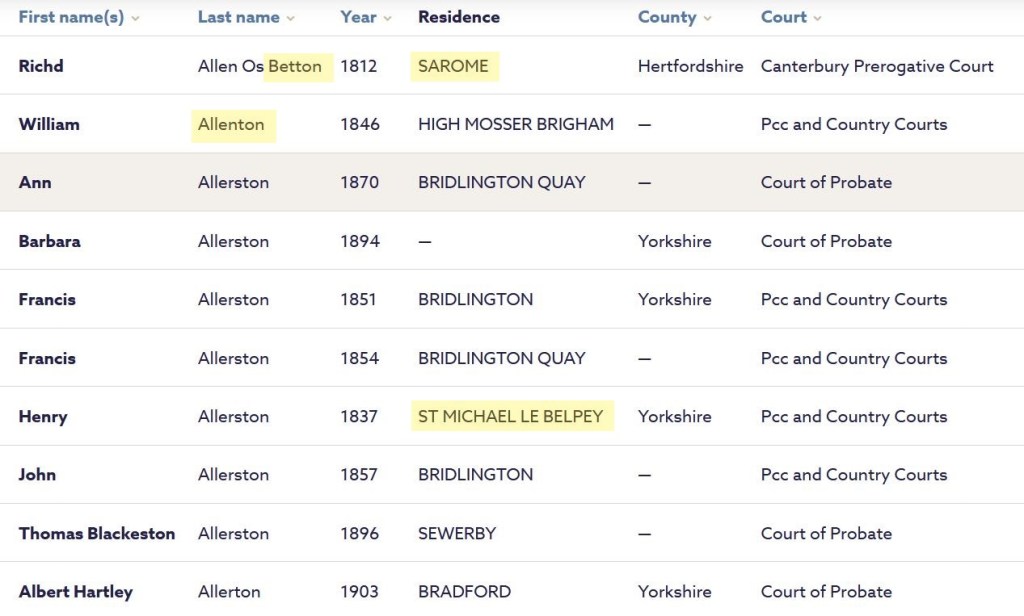

Search was for the surname Al*ton

… as a brief glance at just about any page of results will tell you, the quality of the data in the index leaves a lot to be desired. Let’s take a closer look at the entries on the list here. In addition to the mis-transcriptions (there are four of them in the ten records on the list, highlighted above), the entries in the alphabets also provide useful information which doesn’t appear in the FMP index.

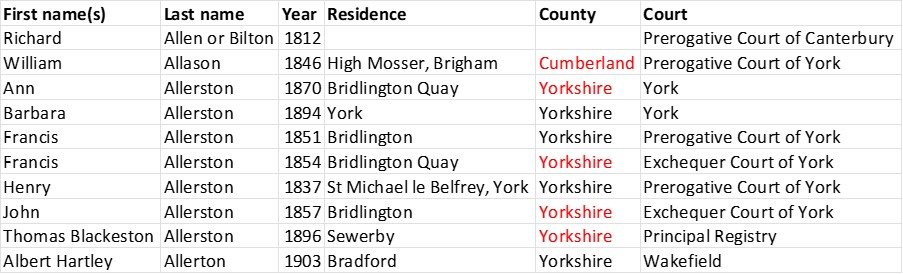

We can quickly update the Findmypast index to look something like this:

I’ve added the counties for the five entries (in red) where no county was given by Findmypast. In fact, the format of the ‘Residence’ data recorded in the alphabets is unstructured and Findmypast have merely attempted to make the information fit with their standard placename ‘fields’ set up – i.e. ‘place’ (usually the name of a parish) and ‘county’. Here, if no county was explicitly recorded, Findmypast have left that field blank.

Again, this would seem like a sensible approach to take, except for one very important point. As ‘county’ is the only ‘place’ field explicitly available for us to search on (you can use the ‘Optional keywords’ field but this is not something that would be obvious to inexperienced researchers) the only way for us to narrow down a search is to use the county option.

And the problem with this is that if you do select a county you are effectively eliminating not only those entries which record counties other than the one you’ve selected, but also all the entries which don’t record a county at all. The result of this is that if you search for the surname ALLERSTON with the county Yorkshire selected, you will get the following results:

Search was for the surname Allerston with the county set to Yorkshire

A bit of research will quickly tell us (based on the information in the ‘Residence’ field on the original search) that the other four ALLERSTONs on our original list were also from Yorkshire (this is NOT specified in the original data), but by entering the county that we’re looking for we’re actually eliminating these entries from the results!

We also need to be aware that the information recorded under the Court heading is taken, not from the individual entries (as you might think would be logical) but from the archival description of the individual document – thus, we get the quite meaningless ‘Court of Probate’ – so in most cases, this information isn’t as specific as it could be. This is particularly true of the details shown in the index for the pre-1858 ecclesiastical courts,

But the biggest problem with the whole of this digitisation project is that a significant amount of the data is actually completely wrong.

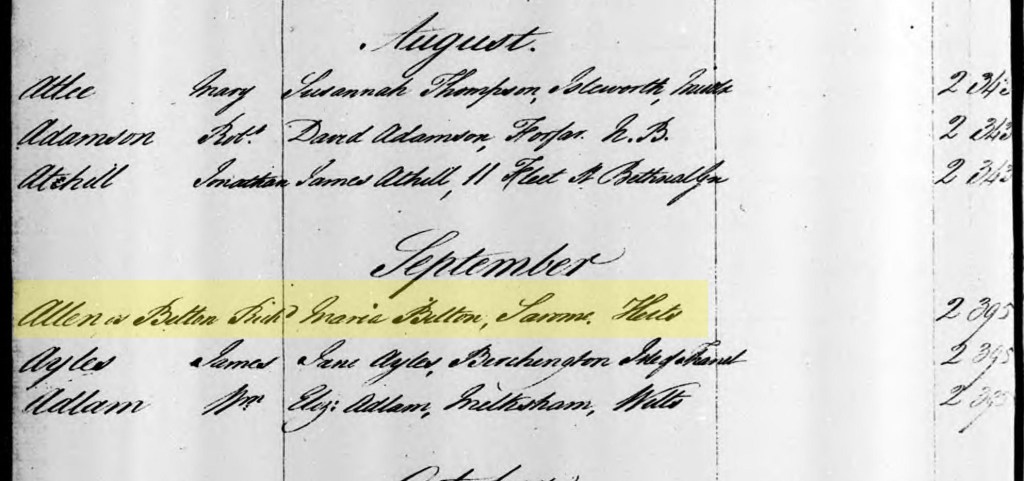

You might have noticed that in the 1812 entry for Richard ALLEN or BILTON (mistranscribed as BETTON in the Findmypast index) his ‘Residence’ was recorded as Sarome, Hertfordshire. (It’s actually Sacome but let’s not worry too much about that.) However, if you look at the entry in the alphabet, you’ll see that, the only residence recorded is that of Maria BILTON, the administrator: Richard’s residence is not recorded.

The National Archives reference: IR 27/21. Accessed via Findmypast

This was, in fact, the case with all of the records between 1812 and 1834. During this period the alphabets record the residence of the executor/administrator, NOT that of the testator/intestate. Additionally, none of the registers relating to letters of administration between 1835 and 1863 record the residence of the intestate (those for the years between 1864 and 1881 are missing).

Let’s try to quantify the extent of this problem…

In the 23-year period between 1812 and 1834, there are nearly 500,000 entries in the database. It’s difficult to come up with an accurate figure for the administrations but there were probably somewhere around 100,000 between 1835 and 1863. So, for approximately 600,000 entries (roughly 18% of the total), no residence is given for the testator/intestate. And yet, a residence for teh testator/intestate is shown in the index against these entries.

Of course, in many cases, the testator/intestate and the executor/administrator are from the same place but clearly this isn’t always going to be true. Indeed, a quick check of a few pages from the 1835 alphabets suggests that we’re looking at somewhere between a third and a half of the testators and executors NOT coming from the same place. In other words, it could be that as much as 10% of the data in the ‘Residence’ field across the whole database is inaccurate! Even a conservative estimate would place the figure at over 5%. And this is NOT because the data has been mis-transcribed but because those responsible for the digitisation project have failed to understand the records that they’re digitising.

To my mind, this is simply not good enough.

In the second part of this blog post, I’ll consider Ancestry’s London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1930 database and its many shortcomings.

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 23 January 2022

Forgot to say Indexes should only be used as a guide or hint not the only information used in a tree.

LikeLike

Love, love, love this article! An excellent example. I don’t have any ancestors in the databases mentioned. But it applies to all databases. I insist on obtaining a copy of ACTUAL document with headings, etc. which helps make corrections on my trees.

LikeLike

Pingback: Best of the Genea-Blogs - Week of 23 to 29 January 2022 - Search My Tribe News

Pingback: When Digitisation Goes Bad II: Death’s Apprentice | Lifelines Research