I realise that I’m running the risk of sounding like a broken record here but it seems like there’s always something else to say when it comes to assessing the work of the major commercial genealogical websites.

Because it’s undeniable that, alongside the many clear and obvious benefits of digitisation there are a number of pitfalls. And one of the most striking of these is the way that the whole process of digitisation robs us of an important sense of context.

Context is vital in any type of historical research and when we’re handling original documents in an archive, we have a tangible and visual relationship with that document. We know what it is, partly thanks to the description in the archival catalogue but also because, in the majority of cases, the document does (or at least, is) exactly what it says on the tin. Somewhere, either on the cover, the spine or perhaps on an internal title page, the document will usually tell us what it is.

Even with microfilm and microfiche, there’s usually some sort of description of what it is we’re looking at written on a label on the outside of the microfilm box or on the little paper sleeve holding the fiche. And in both of these cases (although perhaps less so with microfiche), we get a sense of the physical structure of the document in question as we wind/scan through it.

With digitisation, however, we’re instantly dropped down on a particular page, somewhere in the middle of the document: the physical connection with the document has been almost entirely lost.

If we want to understand what the document is telling us about our ancestor (hint: we really do…) we are now largely reliant on the accuracy of the information captured as part of the digitisation process. Ideally, we would expect a good archival description of the document; some information about the larger collection of which it forms a part (i.e. the archival hierarchy to which it belongs); the archival reference to the specific document that we’re looking at, and a reference to the particular page (if it’s in a book or register) or individual item (if it’s part of a collection of loose papers).

Of course, we can usually browse through the digital images, or, in some cases, select a particular image number so that we can jump to a different part of the document and thereby, to some extent, recreate the process experienced by the previous generation of genealogists when using microform ‘surrogates’.

But I would argue that, while experienced researchers might instinctively pursue this as an option, when it comes to newcomers, this is not a concept that would instantly occur to them as something that’s going to add value to their research. The commercial websites are in the business of making it all sound as straightforward as possible. so they’re hardly about to encourage inexperienced researchers to embark on something as seemingly complex as this is.

So, you’d like to think that the descriptions of the documents and the archival details attached to each individual image would do the necessary job and do it well. But as I explained in my previous blog on the subject, this is, sadly, not always the case. What I want to do now is to illustrate the sorts of challenges that we’re up against, by taking a detailed look at the registers of one particular London parish and comparing the actual documents with their descriptions on the Ancestry website.

St Pancras is a vast ancient parish formerly on the outskirts of London but now very much part of the capital’s urban sprawl. The history of its churches is admittedly confusing as two different buildings, situated in different places, have served as the parish church. And both of them are still in existence today.

The original building, with its claims to late-Saxon (or even Roman!) origins, stands to the north of the present St Pancras railway station. It served as the parish church for the whole of the parish of St Pancras until the building of the new neo-classical church on the New Road (now Euston Road) which was consecrated on 8 May 1822. The original parish church then became a chapel of ease to the new church but quickly fell into disrepair and by 1847 it was derelict.

Public Domain

This was a period of rapid growth in London and the existing parish churches were simply unable to cope with the thousands of people flooding into the capital, in need of spiritual care. The solution was to build new churches in the rapidly expanding suburbs and in the case of St Pancras, the ideal site for one of those new churches already existed in the shape of the old parish church. The building itself required extensive renovation but nevertheless, baptisms began to be performed again at the church from 1848 and marriages from 1859, and by 1863 the restoration work was complete and the somewhat misleadingly-named new ecclesiastical parish of Old St Pancras was formed.

I did say it was confusing but the key to understanding it all lies in the descriptions and archival references provided by the record holders, the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) – descriptions which Ancestry appear to have widely ignored when digitising the records.

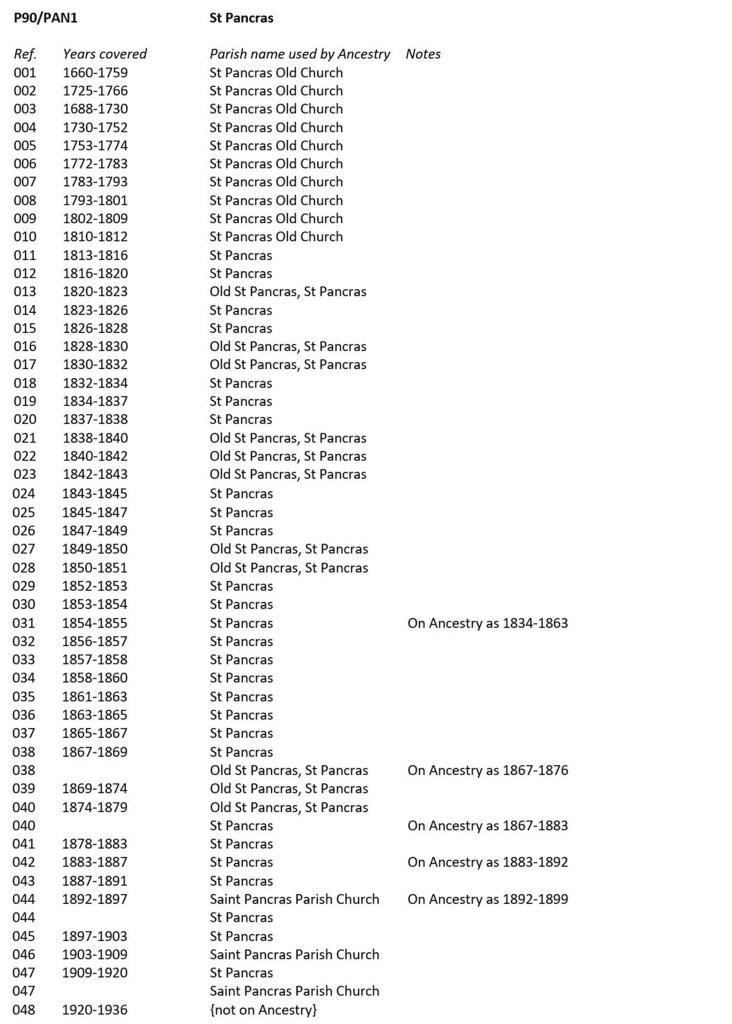

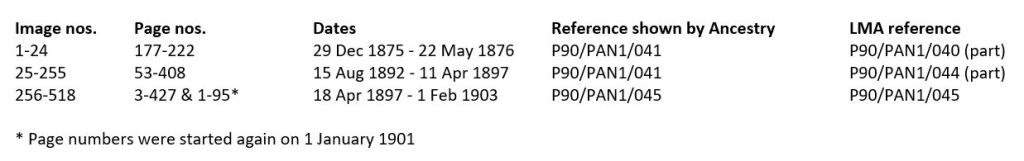

I’ve spent some time today comparing the records on Ancestry with the entries in the LMA catalogue and it’s obvious that there are some serious issues here surrounding nomenclature. The following table lists the baptismal registers for St Pancras parish (i.e. the parish church, whether at its original site up until May 1822 or in its later position since then) and those for Old St Pancras, from 1848 onwards. For each register I have shown the archival reference and the years covered (the LMA catalogue also gives the months in each case but I’ve removed these to make the data clearer). Next to these I’ve added the name of the parish as used by Ancestry.

As you’ll see, no fewer than four different names have been used by Ancestry for Saint Pancras parish, while the ‘new’ Old St Pancras parish has two different names assigned to it, one of which has also been used for the parish church! What the table doesn’t show (due to shortage of space) is that in many cases the references assigned to the registers by Ancestry are also wrong.

You’ll also see that several of the date ranges used by Ancestry are wrong and that a number of the registers are duplicated, which isn’t, in itself a bad thing. But it’s all suggestive of a ‘gung-ho’ approach to the process and this is illustrated by just one example of the extent to which the registers have somehow been mixed up in the course of the digitisation process.

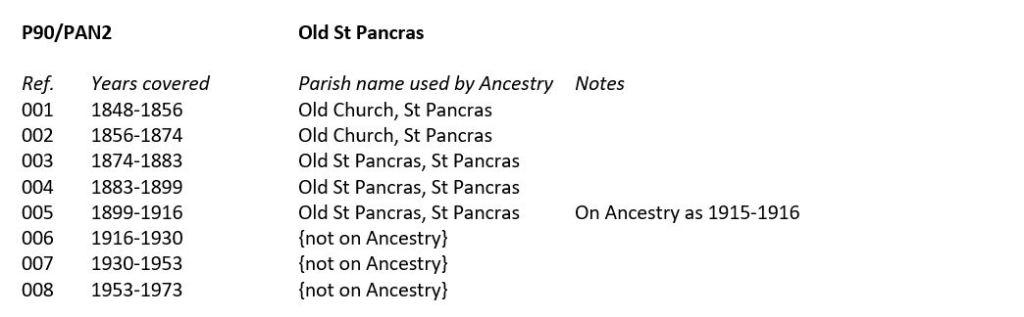

Table 3 relates to a section of digital microfilm described by Ancestry as relating to the parish of ‘Old St Pancras, St Pancras’, and allegedly covering the years 1875-1903. As is so often case with Ancestry, the devil is in the detail. Here I’ve shown the image numbers, the page numbers and the dates covered by the actual registers; the references shown by Ancestry and the actual references according to the LMA catalogue.

So, it does cover the years 1875 to 1903 but there is clearly a gap of 16 years here: a gap which, you’ll be relieved to hear, is covered elsewhere. You’ll also be relieved to know that the first two pages of P90/PAN1/045 are to be found elsewhere.

The worrying thing about all of this is that the deeper you dig, the more problems you find. At least in this case there don’t appear to be any registers actually missing from the collection. There may be some individual pages or small sections missing but we can rest assured that every baptismal register from the parishes of St Pancras and Old St Pancras is included in one or other of Ancestry’s London Parish Register databases.

I spent about four hours investigating this today and I haven’t even started on the marriages and burials. Who knows what horrors are to be found there…? Surely it isn’t too hard to get this right: all they need to do is to use the descriptions that are readily available via the LMA catalogue. And it’s really not even that complicated. We’re dealing with two separate parishes: St Pancras and Old St Pancras. So all of the registers with the reference P90/PAN1 should be described as St Pancras, and all of those with the reference P90/PAN2 should be described as Old St Pancras.

I mean, yes, Old St Pancras is the actually the newer parish but I think that I’ve cleared that up. At least I hope I have…

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 26 November 2021

Pingback: When Digitisation Goes Bad Part I: The Night Of The Living Death Duties | Lifelines Research

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

“Context is vital in any type of historical research” Absolutely… Sometimes we get the images of the front pages of the register (or whatever). Often we don’t. Sometimes we don’t but (usefully) we can find the images on FamilySearch that do have the front pages…

Sometimes the context that we need is elsewhere. I keep using the example of Knowstone and Molland, two Devon parishes that had the same incumbent for many years. When I examined the Molland BTs, the years 1716 and 1718 appeared twice. Based on their appearance, the explanation appears to be that the repeats are actually BTs from Knowstone that had got mixed into the Molland stuff – presumably because the incumbent was the same. But you’d never think of that explanation if you didn’t know he was the same (for which I need to thank people who analysed this stuff long before I did).

PS – I now need to check one of my families who skirted through “St. Pancras” to see what names I’ve used, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for an excellent article. On top of the issues you’ve highlighted there can also be confusion between registers and Bishop’s Transcripts, and then there’s the challenge of how to search a specific parish. Though to be fair, Ancestry isn’t the only site where there is scope for improvement!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Peter. No, they’re certainly not alone on this but as the market leaders they perhaps have a greater responsibility to do things properly – well, you’d like to think so!

LikeLike

Hi David. Thanks for your enlightening article. I think I can see what you are getting at. I am very interested in your piece, as I was born in St Pancras, 11 March 1938. Although I was born there, my family moved to Islington, in time for the 1939 Register, then went with my family to wales during WW2, where my father was stationed. I returned to live in St Pancras, in 1965, and lived there until 1975. My family, both Paternal and Maternal, all come from St Pancras, mostly around Crowndale Road/Mornington Crescent area, so I know Old St Pancras Church, and New St Pancras Church, well. I have yet to find my Baptism record. It could have been from March 1938 until Sept 1939, when I was included in the 1939 register living in Islington, coming under St Mary’s Parish, Upper Street. My Daughter, born 1966, was baptised in Old St Pancras Church, and maybe my son, born 1970. But haven’t found their baptismal records yet.

Thanks again.

Brian

LikeLike

Hi Brian

The record of your own baptism is very unlikely to be available online. Ancestry tend to have a 100-year + cut-off date for birth/baptismal records to protect living people. You would need to contact the London Metropolitan Archives.

Dave

LikeLike

In some ways, I feel fortunate that when I first started researching in my teens, the Internet did not exist. Although I have no wish to turn back the clock, it did give me an appreciation of original records and the need for an accurate description in a catalogue.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I second that. I started out by browsing microfilms/microfiche at the US National Archives branch in Waltham, the Massachusetts Archives, and the local LDS genealogy center.

I still have to go back to those skills in searching early 19th century census records for Maine, where many settlements were grouped together in census tracts, and many are listed in the Ancestry index only under the first-named settlement in the tract.

LikeLiked by 1 person