This blog is dedicated to the memory of genealogist Lorine McGinnis Schulze who passed away recently. I had the pleasure of working for Lorine over the past few years, transcribing several early English wills for her. Lorine’s enthusiasm for the subject was infectious. RIP Lorine.

What would we do without wills? When it comes to making real progress with your research, the difference between working with a family that left lots of wills and one that didn’t is considerable. Even a smattering of wills across a few generations can make all the difference.

And yet, compared with other documents such as birth, marriage & death records, census returns and parish registers, wills (and other associated probate records) don’t get the exposure that they deserve – and as a result, our familiarity with the records tends to be less extensive than it might be.

There’s a lot to say on the subject of wills but I want to focus here on one particular aspect – and it’s an area which I believe hasn’t really been explored enough.

Probate – the act of ‘proving’ a will – is a long and complex process. In order to understand the records that survive to today in the archives of the various ecclesiastical probate courts, we need to familiarise ourselves with the procedure. We don’t necessarily need to develop an expertise in all the legal practicalities of the process (although that would help!) but we do need to grasp some basic concepts.

And one of the most important things to understand is that the process will almost always generate two copies of every will:

- the original, signed by the testator and brought into the court by the executor(s)

- a copy, created by the probate court, entered into a register and known as the registered copy

The original will would have been written on paper or parchment – sometimes by the testator themselves but more often by a professional clerk – and signed by the testator. If the testator was unable to sign his or her name, they made a mark of some sort instead, frequently a cross or an ‘x’. It’s worth noting that the absence of a signature is not necessarily evidence of illiteracy – many wills were written right at the end of the testator’s life, often within a day or two of their death, so a ‘mark’ could simply be the result of ill health. In order to be a legally valid document, the will had to be signed by two or more witnesses and the requirement was that the testator and the witnesses should all sign their names (or make their marks) ‘in each other’s presence’.

The will may then have been deposited into the care of a solicitor or a bank or it might have been kept at home in a safe place but either way, after the testator’s death, the first task for the executors named in the will would have been to take the will to the relevant probate court and ask to be granted the right to administer the deceased’s estate.

Assuming that everything was in order, the executors could then go away and do whatever they were required to do under the terms of the will leaving the will itself in the hands of the court officials. (Thanks to Andrew Millard for pointing out that the executors would have been given a copy of the will which ‘rarely survive unless inherited within a family or among solicitor’s papers.’)

Then, once the probate process was complete, the court made their own copy of the will. The courts kept large registers for this purpose and even in the smaller courts, the clerks were kept busy: by the early 1850s, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC), the senior court of probate in England and Wales, was proving around 8000 wills a year – an average of over 650 per month. The records of the PCC include a total of 2263 registers!

The text of the will would be copied, word-for-word, into the register with the details of the grant of probate added at the foot (usually in Latin before 1732).

So we know that there are (usually) two copies of every will, but how can we use this to our advantage?

In most cases, where a collection of wills has been digitised and made available online, it’s either the registered copies or the originals that we have access to. Occasionally, we can see both but where we can’t, it’s important that we’re aware of the probability that another copy of the will that we’re looking at exists.

When we’re looking at a registered copy of the will, we need to be aware that the ‘signatures’ recorded here are the work of the clerks. To view the actual signatures, both of the testator and of the witnesses, we need to see the original will. The signatures can then be compared with those on other documents to test theories in your research: a match with a signature in a marriage register, for example, could help to prove that the groom and the testator are the same person.

The original will is also likely to include additional details, not all of which are recorded in the register. As part of the probate process, clerks at the court would make notes on the original will. They would routinely record details of the grant of probate (again, usually written in Latin before 1732) including the date and place that the will was proved, the name(s) of the executor(s) and the name of the court official who granted the probate (usually acting as a ‘surrogate’ on behalf of the bishop or archdeacon).

There might be other notes too, particularly if one or more of the executors named in the will was unable or unwilling to perform the duty asked of them. If someone chose to renounce their right to act as executor, the court could appoint someone else in their place and the same might happen if one or more of the named executors had died before the testator. However, as long as one of the named executors was willing and able to take on the role, there would be no need to appoint anyone else.

These details will usually appear in the probate clause in the register but there are occassionaly items which are only to be found on the original. If you’re lucky you might find a note relating to the testator’s death: the date of death is occasionally recorded and if the testator died in unusual or unexpected circumstances (e.g. if they died overseas or at sea) you could be in for a treat.

The original will of Henry Mead, mariner of Wapping, for example, includes a note, written in Latin:

Testator obiit infra duos annos in nave the Adventure Galley in P[ar]tibus Indie Orientalis

The National Archives reference: PROB 10/1313

Which translates as:

The testator died within the last two years in the ship the Adventure Galley in the East Indies

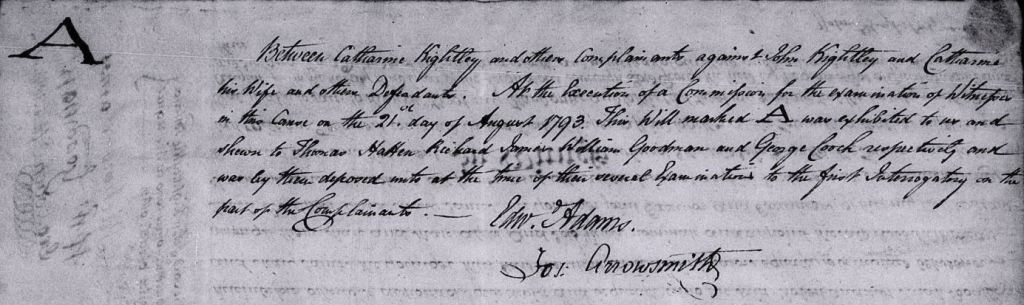

If there was a dispute regarding the will, there might be a note to this effect: perhaps the will was contested by a disgruntled relative or it might have been used as evidence in a court case. The original will of John Kightley of North Crawley, Buckinghamshire for example, includes a note referring to the will having been exhibited in Chancery.

Buckinghamshire Archives reference: DAWf 105/16

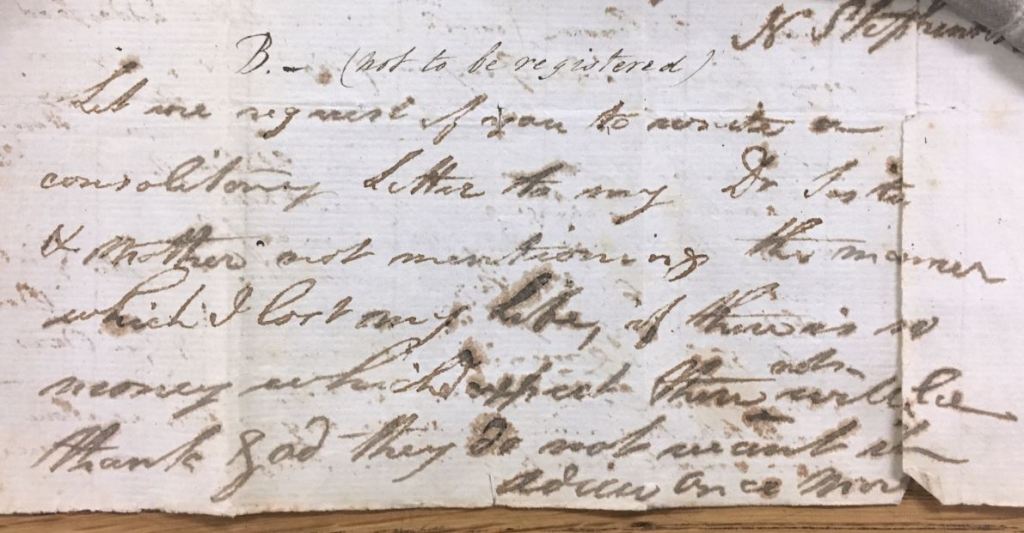

You may even find that the original will was accompanied by some entirely separate documents which the court didn’t feel it necessary to copy into the register. Take the case of Norris Stephenson…

Norris was a Surgeon in the 15th Regiment of Foot and died while on active service in Surinam in February 1806: his will was proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in September 1808. The bundle of documents that makes up his original will comprises three separate documents and on one of these there are two notes (labelled A and B) next to which someone has written the words, ‘not to be registered’. The second of these notes adds considerably to the story of Norris’s life and death:

Let me request of you to write a consolitory [sic] Letter to my D[ea]r. Sister[s] & Mother not mentioning the manner which I lost my Life, if there is no money which it appears there will not be thank God they do not want it.

Adieu once more.

Norris Stephenson died a horrible death from dysentry and evidently didn’t want his sisters and his mother to know. If all we had was the registered copy of the will, this fascinating detail would have been lost.

Due to the manner in which original wills tended to be stored (not quite to the standards that we might expect in a modern archive!) the documents can often be in a poor condition: mould, water damage, rodent/insect damage and even fire could all contribute to the less-than-perfect preservation of our ancestors’ original wills. Charles Dickens, who had an interest in these matters described the offices of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury as:

… an accidental building, never designed for the purpose, leased by the registrars for their Own private emolument, unsafe, not even ascertained to be fire-proof, choked with the important documents it held, and positively, from the roof to the basement, a mercenary speculation of the registrars, who took great fees from the public, and crammed the public’s wills away anyhow and anywhere, having no other object than to get rid of them cheaply … That, perhaps, in short, this Prerogative Office of the diocese of Canterbury was altogether such a pestilent job, and such a pernicious absurdity, that but for its being squeezed away in a corner of St. Paul’s Churchyard, which few people knew, it must have been turned completely inside out, and upside down, long ago.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (1850) Chapter 33

Thankfully, where an original will is damaged (or entirely) missing, it should, in theory at least, be possible to track down the registered copy – registers, by their very nature being more resistant to the ravages of time are more likely to have survived in (relatively) good condition.

Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies reference: 78AW26

Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies reference: 8AR274

And even if the original will has survived intact, the way that they were written, with frequent additions and corrections, and occasionally large chunks of text inserted between two existing lines, can lead to some words and sections being effectively illegible. Again, the registered copy is our friend here.

Of course, in many cases, the two copies will turn out to be effectively identical – and it’s true that tracking down the ‘second’ copy might not prove too straighforward, probably involving a trip to the relevant record office. But even if the potential for a successful discovery is limited, it’s surely always worth checking – you just never know what you might find.

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 19 February 2022

Pingback: Justice for Wills and Probate Documents: – Holt's Family History Research

Pingback: What Did Our Ancestors Do Between The Census Years? – The Chiddicks Family Tree

Thank you for another interesting and informative blog. Wills are one of my favourite sources and I have used signature comparison to differentiate between father and son with same name and occupations on records.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Best of the Genea-Blogs - 20 to 26 February 2022 - Search My Tribe News

Wills of maiden aunts or childless widows are often very useful.

I’ve managed to find two which listed all the relatives they could possibly link to with such helpful listings as “ daughter of my mother by her first husband” or daughter of my father by his first wife” and “daughter of my mothers 3rd husband”.

Then in one I had a listing of a niece of a maiden aunt who she noted was in Aberystwyth, from a Berkshire birth late C18. I really discounted it but then found the whole family there!

LikeLiked by 1 person

House deeds often include extracts of wills which can be quite informative too if the actual wills were, say, lost in bombing in Exeter!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspect that most of the probate documents we hold at the Society of Genealogists a have been executors copies donated by families or solicitors clearing their deeds boxes. You can often see the various official stamps on the outside having been presented as evidence to banks or investments etc.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There was third copy of every will: the one which was issued to the executors. These rarely survive unless inherited within a family or among solicitor’s papers. But if you have one it can be equally useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person