This is the Court of Chancery … there is not an honourable man among its practitioners who would not give—who does not often give—the warning, “Suffer any wrong that can be done you rather than come here!”

Bleak House, Chapter One. Charles Dickens (1852-53)

In 1829, Charles Dickens started work as a court reporter at the Court of Chancery in London. His experiences of the workings of the court – the ‘trickery, evasion, procrastination, spoliation, botheration … [and] false pretences’ witnessed by the young Dickens – gave him the inspiration for the fictional Chancery suit, Jarndyce and Jarndyce, which was to form the background to his legal masterpiece, Bleak House.

Dickens described Jarndyce and Jarndyce as a ‘scarecrow of a suit’ which ‘has, in course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means.’

The Little Church In The Park, by Phiz (Hablot Browne), published in Bleak House. From The Victorian Web

Bleak House was, of course, an exaggeration, designed to satirise the worst aspects of the ‘darkness of Chancery’ for comic effect, but for family historians today, the prospect of researching a case in Chancery can be every bit as daunting as the experience of the Court of Chancery was for Richard Carstone and Ada Clare, the fictional young wards, introduced to us by Dickens.

But it needn’t be. There are certainly obstacles but none of them are insurmountable if you follow my four-step guide to making the most of Chancery records.

1) Understanding the records

The first stage in any research process is to get to know the records you’re working with. With Chancery records, the best place to start is the National Archives’ research guide, which will give you all the basic information you need about the workings of the Court and the records that it created. For more in-depth coverage, I would recommend two books by Susan Moore: Family Feuds: An Introduction to Chancery Proceedings (Federation of Family History Societies, 2002) and Tracing your Ancestors through the Equity Courts: A Guide for Family and Local Historians (Pen & Sword, 2017).

Essentially, each Chancery case (or ‘suit’) could generate five main types of record:

- Pleadings – initial statements made (out of court) by the parties involved in the suit, including Bills of Complaint (by the Plaintiff or ‘Complainant’) and Answers (made by the Defendants)

- Evidence – depositions, affidavits and exhibits submitted to the court

- Decrees and orders – recording decisions made by the court

- Masters’ records – miscellaneous records created by court officials

- Final decrees and appeals

One of the most important concepts to get to grips with is that the various documents created in the course of each Chancery suit were filed by type of record rather than collectively, on a case-by-case basis. This, naturally presents some significant challenges when it comes to tracking down all of the records relating to a particular suit but as many cases didn’t progress beyond the initial Pleadings, this isn’t perhaps as big an obstacle as it might seem.

2) Accessing the records

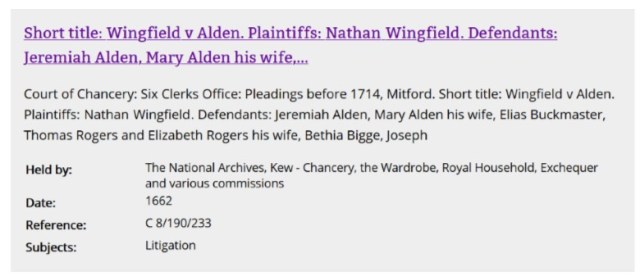

Some good news! The National Archives’ Discovery Catalogue acts as an index to all pre-1875 Pleadings in Chancery and provides the full archival reference along with brief, abstracted details of the suit.

Screenshot from the National Archives’ Discovery Catalogue

The ‘short title’ of each suit (which you’ll need to know when it comes to searching for the other documents) comprises the surname of the plaintiff (or one of the plaintiffs) and that of one of the defendants. The National Archives’ research guide (see above) will tell you all you need to know about other finding aids, both physical and online, including the Bernau Index (available at the Society of Genealogists in London) and the Anglo American Legal Tradition website.

To access the other records in the suit (if any) you’re going to have to acquaint yourselves with the mysteries of the Court of Chancery’s unique filing system! You will also need, either to visit Kew yourself or to employ a researcher to do it for you.

3) Reading the records

There’s no doubt that the handwriting, as well as the sheer size and unwieldiness of the documents can present an obstacle. The Pleadings were written on huge sheets of vellum, known as membranes, often over a metre in width. The documents are usually rolled together and untangling a bundle to find the relevant sheets can be an art in itself. I usually say that the best option when confronted with a difficult-to-read document is to get a good photo of it to work on from the peace and quiet of home. With Chancery records this is sometimes easier said than done.

(I can confirm here and now that, while I was employed by the National Archives, I never climbed onto the tables in the Staff Reading Room to get a better shot of a Chancery document. Not once…)

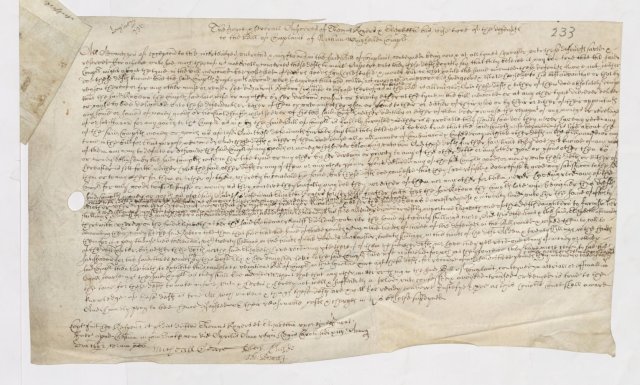

The Joynt & Severall Answeres of Thomas Rogers & Elizabeth his wife. The National Archives reference: C 8/190/233 Wingfield v Alden

Perhaps the best solution, whether you’re able to visit the National Archives in person or not, is to pay for a digital copy to be emailed to you. It’s not cheap, particularly if the suit ran to a number of documents, but the benefits of this approach will quickly become apparent.

Take the case of Wingfield v Alden, which began with a Bill of Complaint submitted to the Lord Chancellor by Nathan Wingfeild of King’s Langley, Hertfordshire in 1661. The Pleadings consist of the Bill of Complaint, the ‘Joynt and Severall Answeres’ of Thomas Rogers and his wife, Elizabeth (two of the Defendants) and a Writ of Warrant issued to Rogers and his wife, demanding their answers to Wingfeild’s original Bill. There is also another, slightly different version of the Bill of Complaint, filed separately from the other documents. Note that the short title of the suit is Wingfield v Alden although the spelling Wingfeild is consistently used in the documents.

The handwriting is undeniably challenging and, for this reason if for no other, Chancery records are definitely not for beginners. But with a little experience and a lot of patience, the text soon becomes (largely) perfectly legible. I can thoroughly recommend the National Archives’ online Palaeography tutorial and there are a number of published works which might help you, notably (if you can get hold of a copy), the excellent Reading Tudor and Stuart Handwriting by Lionel Mumby (Phillimore & Co, 1988).

There are several factors which might contribute to the legibility or otherwise of each document. The physical state of the document is of course an issue, both in terms of the membrane itself and of the ink used, which has sometimes faded badly, or been worn away by use over the centuries. The penmanship of the clerks who created the documents was generally excellent – these were masters of their profession – but the occasional emendation and interlineation can make the text particularly difficult to read. This is where a good quality digital image will reap dividends. The ability to ‘zoom in’ on the trickiest bits of the text is an absolute godsend.

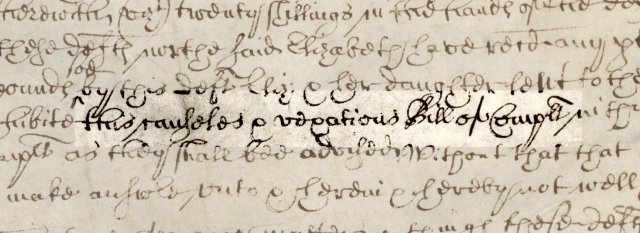

Interlineations can make the text particularly difficult to read.

Detail from The Joynt & Severall Answeres of Thomas Rogers & Elizabeth his wife. The National Archives reference: C 8/190/233 Wingfield v Alden

Every time I approach a Chancery document, with a view to transcribing it, I do so with one emotion: that of utter dread! When you first look at a membrane, complete with all its tightly-packed, monotonous, spidery script, it’s easy to feel that the task in hand is an impossible one and that the best option is to give up there and then, and go and make yourself a nice cup of coffee. A perfectly natural reaction.

So, do just that. Walk away from it, and come back later. Read a few words. Write a few of them down. Read a few more. Write them down. Leave dots or question marks for words that you don’t immediately recognise. And if that’s more than 50% of what you’ve written down, so what? It’s all part of a learning process. The more you read, the more attuned you’ll become to the clerk’s handwriting. And one thing that the clerks always were, is consistent. If they wrote a capital B once, they wrote it exactly the same the next time. So once you know that that’s what that character is, you can start to replace some of those dots and question marks with real letters.

Read back what you’ve written and try to make sense of it; try to think about what type of word the missing one is. Is it likely to be a verb or a noun? It’s like cracking a code. You start with nothing and gradually, over a few hours, a complete document begins to emerge. You’ll almost certainly have a few question marks remaining in your ‘final’ version of the text. Even the most experienced and accomplished transcriber will find that there are occasionally some words that they just can’t work out. Surnames and place names (particularly names of unfamiliar fields or pieces of land) are always going to cause problems but it really doesn’t matter. The important thing is getting the bulk of the document accurately transcribed.

The particular method you use for your transcription is entirely up to you but I would advise you to remember that at this stage, what you’re trying to do is to write down, as faithfully and accurately as you possibly can, what the clerk actually wrote. This is not an editorial process – that’s for later.

Personally, I find that it helps to number each line of the text. If you have the technology or knowhow to do so, you should also add the line numbers to a copy of the digital image itself. If nothing else, this will help you to locate a particular phrase or word if you need to come back to it. Interlineations (the practice of inserting additional text above an exisiting line of text) can provide challenges to transcribers, not just in terms of the readability of the interlineated text, which is by its very nature, going to be limited by its size, but also as a question of how to present such text in your transcript. My preference is to use the ‘caret’ character ^ to indicate where the interlineated text begins and then to write the interlineated text as a superscript. I also use Strikethrough to indicate where text has been written and then ‘removed’.

4) Interpreting the records – and telling the story

You’ll come across a number of unfamiliar words and phrases in the text: the plaintiff refers to him or herself as ‘your Lordship’s Orator’ while the defendants refer to the plaintiff as the ‘Complainant’. If the suit is brought on behalf of an infant (i.e. someone under the age of 21) the person responsible for bringing the suit to Chancery is known as their ‘Next Friend’. This will all make sense if you’ve read up on the workings of the court.

Eventually you should end up with a transcript that you’re at least relatively happy with. But it’s an on-going process; you’ll want to constantly revisit the text and each time you do, you’ll probably find that you’re able to fill in additional gaps.

An exercise which I find particularly useful is to play around with the text and sort it (in a new document!) into meaningful paragraphs. You’ll have noticed that, as with most legal documents of the period, punctuation marks are at a premium – in other words, almost non-existent. However, it should still be possible to identify each individual clause and to add the appropriate punctuation so that you can transform something like this:

19. Said Compl[ainan]ts money or goods as aforesaid And this defendant Elizabeth Rogers for herselfe farther Saith that the Said Rebecca the Compl[ainant]s late wife being her this def[endan]ts

20. Mother ^ came ^^ severall tymes since her intermarriage with the pl[ain]tif ^ to this def[endan]t & Complayned to her for want of moneys & other necessaryes by reason of the said Compl[ainan]ts unkindnes to her whereupon this defendant did without her husbands privity or knowledge & at her the Said Rebeccas earnest request & intreaty lend unto her the Som[m]e of Forty

21. Shillings ^ & sev[er]al tymes furnished her with other necessaryes of p[ro]vision for Supply of her wants And Shee the Said Rebecca afterwards standing in need of more moneys as Shee alleadged did earnestly importune Elizabeth one of this def[endan]ts daughters to furnish her

22. therewith whereupon the said Elizabeth at her the said Rebeccas request did lend unto her the Som[m]e of twenty Shillings more, And this defendant & the Said Elizabeth afterwards

Into something like this:

And this defendant, Elizabeth Rogers, for herself further saith that the said Rebecca, the complainant’s late wife, being her this defendant’s mother, came several times since her intermarriage with the plaintiff to this defendant and complained to her for want of moneys and other necessaries, by reason of the said complainant’s unkindness to her. Whereupon, this defendant did, without her husband’s privity or knowledge, and at her, the said Rebecca’s, earnest request and entreaty, lend unto her the sum of forty shillings, and several times furnished her with other necessaries of provision for supply of her wants.

And she, the said Rebecca, afterwards standing in need of more moneys, as she alleged, did earnestly importune Elizabeth, one of this defendant’s daughters, to furnish her therewith. Whereupon, the said Elizabeth, at her, the said Rebecca’s, request, did lend unto her the sum of twenty shillings more.

You can even break the text down further and create a ‘modern’ version:

Elizabeth Rogers said that Rebecca Wingfeild (her mother) had visited her on several occasions since her (Rebecca’s) marriage to Nathan Winfgeild, saying that she was in need of money etc., due to Nathan’s unkindness to her. Elizabeth lent Rebecca 40 shillings, without telling her husband.

Rebecca also went to Elizabeth Rogers’ daughter, Elizabeth, and asked her for money. The younger Elizabeth lent Rebecca (her grandmother) a further 20 shillings.

Naturally, you’ll want to sort the documents into chronological order and once you’ve done that, you can really begin to understand the whole story, from start to finish.

The case of Wingfield v Alden is a relatively simple one which, as far as I can tell, never reached the Court of Chancery itself. The whole suit appears to comprise two versions of Nathan Wingfeild’s Bill of Complaint, the Writ of Warrant and the resultant ‘Joynt and Severall Answeres’ of two of the defendants, Thomas Rogers and Elizabeth his wife. Once I’m able to do so (I’m writing this in the middle of the coronavirus lockdown) I’ll take a trip to Kew and see if I can find anything in the Decrees and Orders or even a Final Decree.

The story can be summarised as follows:

Sometime around 1656, Nathan had entrusted his wife, Rebecca, to give certain friends, neighbours and relatives, £100 and some of his goods and ‘household stuff’ on the understanding that they would dispose of the money and goods to Nathan’s benefit. Rebecca had died in May 1661 and now Nathan wanted to know what had happened to the money and goods and wanted the friends, neighbours and relatives to repay the money (with interest) and to return the goods to him. He had evidently approached each of them and asked them to do so but they had denied that they’d ever received anything from Rebecca. Unfortunately, Nathan had no witnesses who could prove that Rebecca had done what he claimed and his only course of action now was to sue them in Chancery.

We only have the ‘answer’ of two of the defendants, Thomas and Elizabeth Rogers. Elizabeth, as we’ve seen from the extracts above, was Nathan’s step-daughter and this is the sort of genealogical detail which can make Chancery documents so rewarding. Thomas and Elizabeth denied receiving anything from Rebecca and went on to claim that they had in fact given her money. Their ‘answer’ culminates in the wonderful statement that:

… they have more reason to sue the said Complainant then hee hath to exhibite this causeles & vexatious Bill of Complaint in this honourable Court against these defendants …

‘… this causeles & vexatious Bill of Complaint’

Detail from The Joynt & Severall Answeres of Thomas Rogers & Elizabeth his wife. The National Archives reference: C 8/190/233 Wingfield v Alden

Chancery suits are all about the lives of ordinary people. Sometimes those people can find themselves buried by the workings of the court which, in Charles Dickens’ own words, ‘so exhausts finances, patience, courage, hope, so overthrows the brain and breaks the heart’. But more often than not, in amongst it all, the voices of our ancestors can be heard and it’s our job as family historians to ensure that their stories are rediscovered, re-told and preserved for posterity.

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 29 March 2020

Hi David. I really enjoyed that, very clearly explained, thank you. I’m looking for a case in Chancery that was settled in 1904. I can see in the TNA Guidance conflicting info that 20th cent. cases may have largely been destroyed, with only samples kept. If I cannot find the case listed in Discovery, will it have gone, or is it buried in a ledger somewhere that isn’t indexed by every name in it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t say that I’ve ever used Chancery records as late as this but as far as I can tell, it’s only some records from the mid-1920s and later that have been ‘weeded’. Everything should survive for a 1904 case. You’ll need to go to Kew to do it all, and you should start with Entry Books of Decrees and Orders (J 15) which cover the years 1876 to 1955. The Pleadings (1876-1942) are in J 54 and the Affidavits (1876-1945) are in J 4.

LikeLike