Those of you who follow me on Twitter will know that I’ve embarked on a virtual journey this year, tracking down the places connected with my ancestors’ lives (I’ve ‘borrowed’ my wife’s as well) and I’ve been tweeting about a different one each day, using the hashtag #365AncestralPlaces.

In the process, I’ve learnt a lot about some of the previously less-explored parts of my family tree and I’ve also made some surprising discoveries.

I didn’t want to limit myself to the places that they lived and died in so I’ve been including their schools and workplaces, the churches that they were baptised and married in, and the cemeteries and churchyards that became their final resting places.

The question of what constitutes a ‘place’ is something that I find endlessly fascinating. In family history terms it can mean anything from a specific building to a particular country or even a continent! The many stages in between might include a row of houses or cottages, an unspecified address in an urban street, or a small hamlet or village. Perhaps all you have is the name of the parish, or the town or city where your ancestor was born or you may know nothing more than the county.

What I’ve been trying to do, wherever possible, is to identify the actual buildings, and I’ve spent many a happy hour browsing maps on the magnificent National Library of Scotland Maps website (it’s not just about Scottish maps!) and comparing them with what’s on the ground today via the remarkable technology that is Google Maps Street View – exactly how have we have arrived at the place where we take this sort of thing for granted?

As a family historian, I’m always looking at ways of putting flesh onto our ancestors’ bones; We need to stop thinking of them as mere names and dates on a family tree and to start seeing them as real people who lived real, complex three-dimensional lives and we can achieve this by carrying out detailed investigative research.

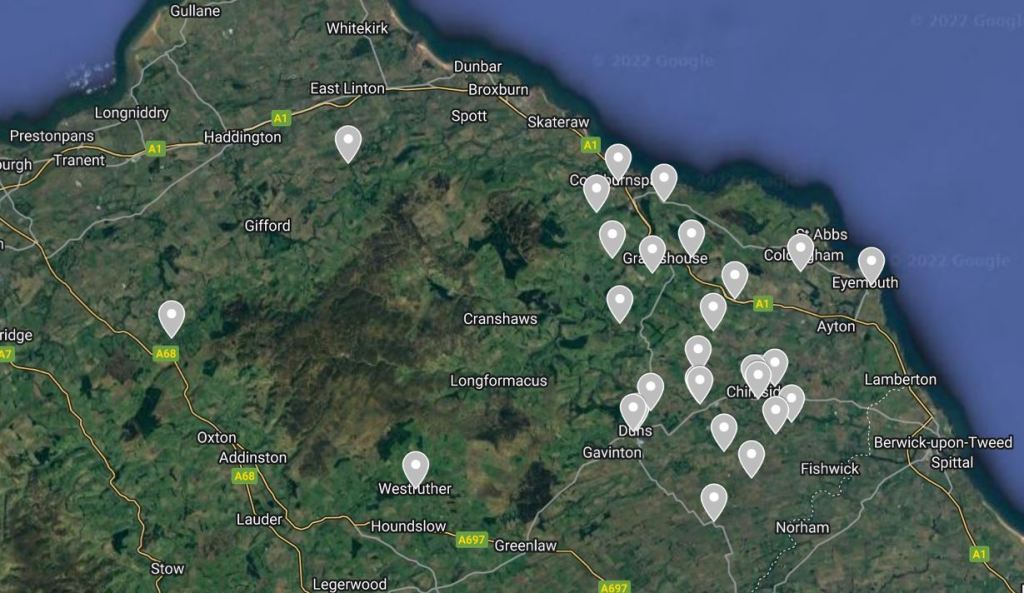

My #365AncestralPlaces project has encouraged me to focus on the importance of our ancestors’ places in their lives. Understanding the moves that they made and when they made them, listing those moves chronologically and plotting them on a map, looking for patterns and trends; all of this can help us to frame the questions that we need to ask if we want to get a feeling for the people behind the names and dates.

Of course we can’t always answer these questions and the documents can only ever tell us part of the story but it’s become increasingly clear to me over the course of the past ten months what a pivotal role places play in our ancestors lives.

The process of identifying the individual buildings has sometimes proved to be quite challenging; all-too-often the documents lack the necessary detail but in most cases I’ve managed to get there eventually.

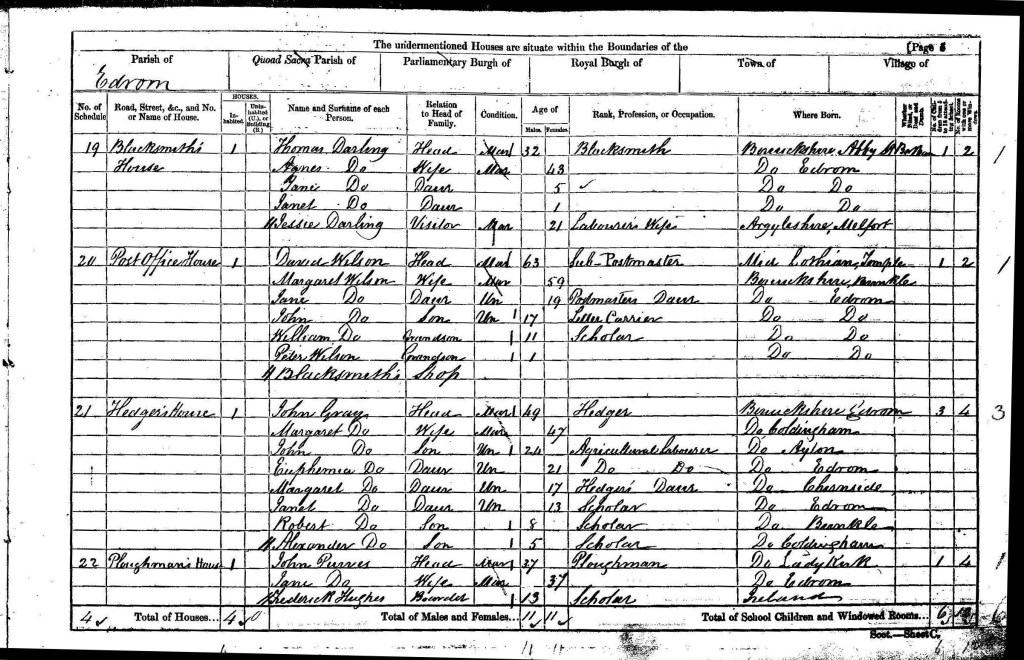

Take my 3x great grandparents for example. John Gray and his wife Margaret (née Liddle) were living in the Berwickshire parish of Edrom in the south-eastern corner of Scotland at the time of the 1861 census.

John was a hedger – a farm worker with well-defined and specific responsibilities, which included the task of planting, maintaining and repairing hedges but could also involve the supervision of ploughmen and other farm labourers and field workers.

The 1861 census records the Gray’s address as ‘Hedger’s House’ which might be more useful than many addresses that you get in mid-19th century census returns but doesn’t, in itself, offer too many clues as to its actual location. In fact, it bears all the hallmarks of a ‘temporary’ name, one that was used by the enumerator as a way of identifying which house he was dealing with, and perhaps used locally, but not the sort of thing that you might expect to find engraved in the lintel above the front door. The impression you get here is that the name of the house would probably last no longer than its occupation by the hedger.

And this impression is confirmed by the names of the other houses entered on the same page of the census. The household at the top of the page featuring a blacksmith is named ‘Blacksmith’s House’; the sub-postmaster’s house comes next and it’s listed as ‘Post Office House’. Then we have John Gray, the hedger at ‘Hedger’s House and finally, the ploughman, listed with his family at the ‘Ploughman’s House’.

At first glance it doesn’t look like there’s much to help us here but the post office is exactly the sort of clue we’re looking for. Buildings such as this, along with pubs and shops, have a permanency about them which the other addresses on the page are lacking: it shouldn’t be too hard to find out exactly where in Edrom the post office was.

The draughtsmen and cartographers employed by the Ordnance Survey were busy in the 1850s, producing the first series of large scale maps to cover the whole of the country. The 25-inch-to-the-mile (1:2500) maps for the county of Berwickshire were published in the latter half of the 1850s, with the stunningly beautiful, hand-coloured versions appearing in 1858, displaying the Berwickshire countryside in vibrant detail.

As a result of this labour on the part of the Ordnance Survey, we have a detailed map of the parish of Edrom drawn up within a few years of the 1861 census and we can easily find the location of the post office, across the road from the manse, on the corner of the road that leads up to the parish church.

We can also see that the building immediately to the east of the post office is labelled ‘Smithy’, tying in perfectly with the entry for the ‘Blacksmith’s House’ which immediately precedes the post office in the census. So it doesn’t take too much imagination to reason that the enumerator was following a logical route taking in the smithy before moving onto the post office and that the next building he came to would be the one just around the corner from and to the north of the post office – and that this is the building described as the ‘Hedger’s House’ and occupied by my Gray ancestors in 1861.

The buildings are still there today and can quickly be found on Google Maps: the Old Post Office on the corner (now a residential property but note the tell-tale sign of the post box which we can just make out on the other side of the road against the hedge) with the short row of cottages stretching northwards to the old school.

And this is therefore (surely?) the actual building that my 3x great grandparents were living in at the time of the 1861 census. It’s a fairly humble abode but it was home to John and Margaret Gray and thanks to the wonders of the internet I can view it online from the comfort of my own home.

Of course, not all of our ancestors’ homes, schools and workplaces have survived but when they have, I would encourage you to make every effort to identify them. The same process which allows us to breathe life back into our ancestors can also help us to place them in the context of their communities and allow us to say not simply that they were born in this or that parish but that they lived here, in this particular house.

It’s all part of what I hope is the aim of all serious family historians: to attempt to tell the life stories of our ancestors and to preserve their memory for future generations.

If we’re lucky, we can add an extra dimension to the search for our ancestral places by finding a contemporary (or roughly contemporary) image of a particular place. In this case, I was able to find a photo of the Old Post Office in Edrom dating probably from the late 19th or early 20th century. https://tour-scotland-photographs.blogspot.com/2018/02/old-travel-blog-photograph-post-office.html

The building to the right of the post office is the old smithy and we get a tantalising glimpse of the cottages to the rear and the old school. This is, of course, long after the Grays had moved away from the area but despite the passage of 50 years or so we can still get a taste of what life must have been like for my mid-Victorian ancestors in this quiet corner of the world.

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 17 October 2022

Fascinating! My husband’s 3rd g-grandparents also lived in Edrom. William and Margaret Dickson were listed in the 1861 census living in “Weaver’s House”, which appears to be two doors down from the “Schoolhouse Cottage” where Margaret Cowper, the schoolmistress, lived. Would that have been near the school also?

LikeLike

I’m sure they must have known each other!

LikeLike

Local newspapers often put your ancestor in their place too, not just BMD announcements – at church or a funeral or political party meeting or, dare I suggest, in trouble with the law!

LikeLike

I found this very interesting. I have been researching my family for more than forty years and, over that time, have become more and more interested in placing them within their communities and finding out more about them as real people. It helps that I was born and grew up in the village (albeit now part of an urban sprawl in the West Midlands) where many generations of my ancestors lived out their lives, so I am familiar with the streets and paths and some of the buildings they knew, built and worked in. Over the past couple of years, despite living 100 miles away for nearly forty years (though I do just happen to have settled in the County where my other main branch came from!), I have been helping to transcribe Parish and Nonconformist Registers which has added to my knowledge of the village and how it functioned, the hamlets which made it up before addresses were formalised, the pubs, shops and chapels and the industries which provided many with a living.

Recently someone posted on a ‘local memories’ Facebook page, asking where a particular hamlet had been and I realised that two of the local hamlets had completely disappeared in the last 100 years, their locations quarried out of existence. Since many of my ancestors had lived in those hamlets, I was rather sad to realise that these places were disappearing from local memory.

So, I have a new project to keep my brain alive in my retirement – I have done the Pharos course on and I am working on a ‘One Place Study’ on these disappeared places and, as time permits, I may well extend it to other places nearby. The availability of censuses, church records and maps online makes possible the gathering of information in a way we did not dream of even twenty years ago. I have recently been reading your (and Peter Christian’s) book the Expert Guide to the Census and nodding as I read your descriptions of researching before the internet! Obviously, I do not have your vast knowledge to draw on but it appears we have ended up with similar thoughts at this point and I shall be using some of your ideas here about maps and how to use them, thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback Glenys. I think that the days of ‘ancestor collecting’ are numbered – at least I hope they are!

LikeLike