31 microblogs written and published during the month of August 2024, each one focussing on a different discovery that I’ve made over the years in my own family history…

Thirty One

I’d always known that my Grandma was illegitimate and I’d always steered clear of asking her too much about her childhood. She was an only child and she’d been brought up by her mother, who lived with her until her death in 1958. About her father, there was complete silence…

So when, one day in the early-to-mid 1980s, as we were wandering around an Edinburgh cemetery looking for family gravestones, she suddenly asked me, ‘Did you know that I knew my father?‘, I knew instantly that my family history research had taken on a new dimension and that new opportunities were about to open up. If she hadn’t told what she knew, one eighth of my family tree would still be a mystery to me today, although I would have had some interesting DNA matches to follow up!

Forty years later, I’m still discovering new things about her father’s family and I am eternally grateful to my wonderful Grandma for trusting me with her remarkable story.

Thirty

There can’t be many of us who have been able to identify the very day on which our ancestors first used their family name but my wife is fortunate enough to be able to do just that, thanks to a discovery we made a few years ago. We were aware that her German Jewish ancestors would have once used the Hebrew patronymic naming system and that at some stage they had ‘adopted’ the surname Schwarz. In fact, we discovered that they had been obliged (forced?) to use it.

In 1794, the ‘Palatinate’ territories on the west bank of the Rhine were occupied by French revolutionary forces. The occupation lasted until 1813 and during the intervening 20 years, French rule, and French legal and administrative systems were gradually introduced. One significant aspect of this was that all Jewish inhabitants were to use family names. And back in 2020 we found a remarkable document, recording my wife’s ancestors taking on the name Schwarz.

Before the Mayor of the Commune of Essingen, Canton of Landau, Arrondissement of Wisembourg, Department of Bas Rhin, it is presented Josephe Salomon, who said that he took the name of Schwarz for (his) family name, for (his) forename kept Joseph and signed with us the 25th October 1808.

Twenty Nine

I mentioned a few days ago, the Chancery documents which told me about My 3x Great Grandmother being sent to Buckingham in 1804 to live with Mrs Hutton, a friend of her mother’s (see Twenty Four). Mary Ann Port was then about 16 and it’s clear from other records that she had been sent to Buckingham to work as a governess to Henrietta Hutton’s four young daughters. The youngest, Jane Lucy, was born in 1804.

The four girls would have grown up with Mary Ann as a familiar figure but, without any specific sources available to me, it’s impossible to say anything about their relationship. I already knew that Henrietta had made provision for Mary Ann in her will – to my friend Miss Mary Ann Port during her life [an] annuity of twenty pounds – which suggested that this was more than just an employer/employee relationship but a discovery I made about four years ago, provided me with evidence that it may have been even more than that.

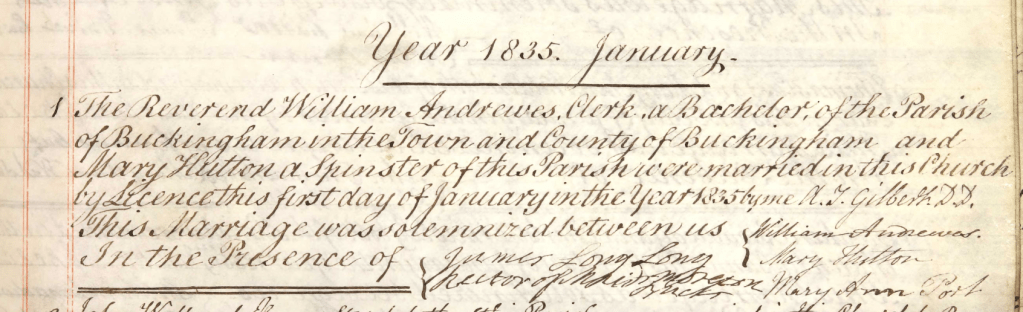

On New Year’s Day 1835 Mary Hutton, the second daughter of Henrietta and her husband, the wonderfully-named Reverend James Long Long, married the Reverend William Andrewes at the fashionable Westminster parish of church of St George Hanover Square – and Mary Ann was one of the witnesses! Seeing her signature in the parish register and knowing that she must have meant something to Mary Hutton, was one of the most moving experiences I have ever had in my many years as a family historian.

City of Westminster Archives Center ref: STA/PR/2/2 p/454

Twenty Eight

Amongst the many treasurers I inherited from my granny after she died in 1991 was a small, plain notebook. It was her father’s and it dates from the early 1890s at a time when he was trying to set himself up as chemist. There’s a beautifully decorative title page on which he wrote the words ‘Receipe Book’; it looks like he’d originally written ‘Receipt’ and (rather clumsily) changed the ‘t’ to an ‘e’ which, in the context made a bit more sense but suggests a lower standard of literacy than I believe he possessed.

My Great Grandfather, David John Davidson, (after whom I am named!) is a fascinating character and his ‘Receipe Book’, comprising 65 pages of medicinal ‘recipes’, remedies and cures for common diseases of the day, is one of my most precious family heirlooms. But the notebook took on a different meaning to me when I discovered, about three quarters of the way through, two pages written in shorthand. I’ve had it transcribed and, although a few words are unclear it tells a fascinating story of a relationship which seems to have been in trouble (‘No one will have to account for my misdeeds but myself…’ and ‘I think I have always treated you in a manner that was right, but if you are desirous of our engagement being brought to a termination I shall not withold [?] you…’). It’s signed by David and although no names are mentioned it seems to be addressed to his future wife, my Great Grandmother. It appears that they resolved whatever difficulties they had as they were married in July 1894.

Twenty Seven

As well as providing us with some fascinating research opportunities, my wife’s German ancestry, specifically the Jewish side, presents us with some emotionally difficult challenges. Confronting what happened relatively recently to some of my wife’s close ancestors, events which had a direct impact on people that she knew well, is never easy.

The experiences of her second cousin, Johanna Brandeis, for example, have the makings of a fascinating story, but it’s all too close to home. My wife knew her Aunty Jeanne well and she knew some of her story but over the years, as we’ve discovered more details, it’s become almost too much. Suffice it to say that she and her husband spent years trying to escape the reaches of the Nazi regime, and ultimately succeeded, but the lengths they went to…! They were aided by numerous friends, colleagues and family members and must have been particularly grateful to the person who made their fake ID cards. My daughter has written part of the story, which you can read here.

Twenty Six

We’ll come to the story of my grandma’s father soon. One of the most remarkable aspects of it was the discovery of the will of his wife. Edith Bushnell is a shadowy character; I know that she was born in Birmingham and that she married my Great Grandfather, Frederick Thomas Port, in 1872 in Harborne, Staffordshire but not much more.

Frederick and Edith moved to Edinburgh where in the early 1900s they employed a woman called Margaret Howland as a housekeeper – the story is that Edith was disabled but I have no evidence to support that. Margaret Howland was my Great Grandmother and she and Frederick had an illegitimate daughter, my grandma.

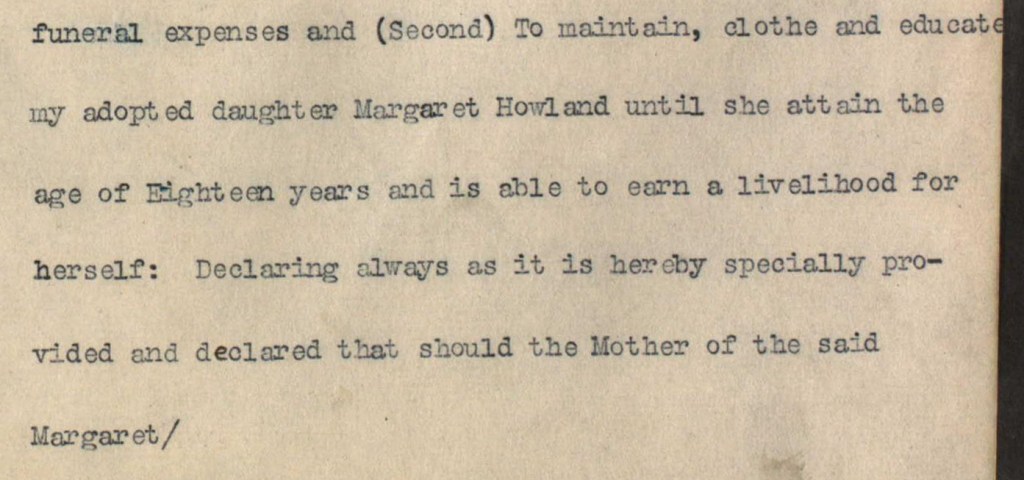

After Frederick’s death in 1917, Edith wrote a will in which she left the following instructions to her executors:

To maintain, clothe and educate my adopted daughter Margaret Howland until she attain the age of Eighteen years … [but] should the Mother of the said Margaret take her from the Guardianship of the said [executors] … the said parent shall have no monetary claim against them … or my estate

‘My adopted daughter‘! I don’t know the precise words that my Great Grandmother used in reply but I imagine that they wouldn’t have been suitable for polite company…

Twenty Five

In the early 1980s my wife and I visited the Rathaus in Offenbach-an-der-Quiech to see what we could find out about her Schwarz ancestors who had lived in the village of Essingen before they moved to Landau. We struck gold as register after register was brought out and names and dates were added to the then barely budding family tree.

The best discovery of all was the record of the marriage of my wife’s 2x Great Grandparents, Izaak Schwarz and Sara Dannheisser who had married in Essingen on 29 January 1844. We were able to get a photocopy of the document which was a typical German marriage certificate, bursting to the seams with genealogical detail and, thanks to the handwriting, presenting us with a huge challenge, which kept us busy for the next week or so.

We’d probably managed to interpret about 75% of it and were really pleased with ourselves. It was, we felt, quite an achievement and we gave ourselves a big pat on the back. However, when we got back home and showed it to my mother-in-law, we felt a bit less smug as she stood there and read the whole thing without pausing…

Twenty Four

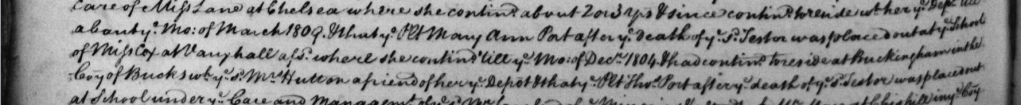

On 4 April 1799, Samuel Port, my 4x Great Grandfather, died, leaving a will in which he appointed three friends as trustees. With hindsight he would probably have taken a different approach as the three men failed to perform their duties according to the terms of his will. And the result of this was a family historian’s dream: a Chancery case that ran for almost eleven years, generating an enormous amount of paperwork.

Samuel didn’t explicitly name his children in his will but they are fully identified in the Chancery documents – and I’ve made some amazing discoveries. I learnt, for example, from an entry in the Decree & Order Books from July 1813, that my 3x Great Grandmother Mary Ann Port, ‘was placed out at School from the time of the death of the said Testator [i.e. Samuel] under the Care of Miss Cox at Vauxhall where she continued until about the Month of December 1804 and had since continued to reside at Buckingham in the county of Bucks with Mrs Hutton a friend of the said Plaintiff Elizabeth Port [i.e. Mary Ann’s mother]’.

Genealogical gold dust!

The National Archives ref: C 33/601 f.1004v

Twenty Three

When I first visited Orkney about 40 years ago and I made sure that as part of my itinerary I paid a visit to my 3rd cousin twice removed, Alexander ‘Sandy’ Taylor Annal. I had discovered that he was the keeper of the family stories and I had also heard that if you wanted to see the 1821 census for South Ronaldsay, Sandy was your man.

When we arrived at his farmhouse and got talking, I mentioned the 1821 census, and I was, to say the least, slightly distressed when he wiped his hands on his jumper, reached into a kitchen drawer and removed an old document from its depths. This was the only copy of the census and it wasn’t exactly being treated with the most up-to-date archival practices in mind!

Nevertheless, it survived and, following Sandy’s death in 2007 (agonisingly, just five months short of his 100th birthday) we arranged to have it deposited in the Orkney Archives. The document itself has a fascinating story involving several members of the Annal family – it had been saved from a bonfire by Sandy’s grandfather! – and it’s now freely available via Findmypast.

Twenty Two

My wife’s German ancestry is a constant source of fascinating new discoveries. We’ve tended to focus on her mum’s Jewish ancestors as they’re the ones that come from the part of Germany that we’re most familiar with. But every now and then her north German protestant ancestors throw up a surprise or two. We’d known for years that her Buck ancestors came from the old Hanseatic town of Stendal in the former Prussian province of Saxony. But a chance discovery a few years ago opened up a whole new area of research and provided us with a remarkable story.

Before settling in Stendal the Bucks had lived in a small village called Hohengrieben about 60km to the west. And Hohengrieben turned out to be a planned settlement, established in 1748 by Frederick the Great to accomodate ten Calvinist families, refugees from Roman Catholic Bavaria. And the Bucks were one of those families!

Twenty One

I mentioned on day thirteen the close links between the Orkney island of South Ronaldsay and the Hudson’s Bay Company and the large numbers of young men who went out to work in the “Nor’ West”. One of these men was a distant cousin of mine called Magnus Annal.

His is a difficult story to tell and it’s one with an unsettling ending. As a servant of the Hudson’s Bay Company working in North America in the late 18th century, Magnus was effectively part of an invading force, the presence of which was actively resisted by large sections of the local population.

In the summer of 1794, Magnus was left in charge of a trading post called South Branch which on 24 June was attacked by around 100 horsemen of the Gros Ventre tribe. Magnus, his wife and child and all but one of the occupants of the post were killed; the story was later told by the one survivor. Part of me wants to discover more, part of me finds the whole episode too difficult to confront. Even the language used on the memorial placed at the site of the massacre is distinctly troubling…

Twenty

It’s the nature of family history research that some discoveries are made quickly while others take years of careful research. Today’s story fits in the latter category. After first discovering the existence of my Great Grandfather, Frederick Thomas Port, sometime in the early 1980s, it took me 40 years to find his last resting place.

He’d lived in Edinburgh since moving there from his native England in the 1880s. He worked as a salesman and in 1917 he found himself on business in Brighton where he was knocked off his bicycle, run over by an omnibus and later died of the injuries he sustained. His body must have been returned to Scotland as I discovered just two years ago that he was buried in Edinburgh’s, Dean Cemetery.

Author’s photograph © 2022

Nineteen

My grandma (my dad’s mum) died on New Year’s Day 1990, aged 83. She left me with many happy memories of days spent together; walking round the corner to catch the bus for trips into Edinburgh, days at the Zoo and the Botanic Gardens, walks up Corstorphine Hill. We talked about family but I was always careful not to probe too deeply into areas that she might not want to discuss – of course, I wish now, that I’d been braver…

Alongside the memories, perhaps the best things she left me was a huge collection of family photos. I know most of the people in them but there are also several who crop up regularly who are completely unknown to me. Again, I wish I’d asked her but most of them were discovered after she died.

Here are four of my favourites…

Eighteen

Most of my mother’s maternal grandfather’s family came from the Scottish Border county of Berwickshire and most of them were agricultural labourers of some sort or another. In fact, I assumed that they all were – until a few years ago, when I made a surprising discovery.

My 3x Great Grandmother, Elizabeth Robertson was the daughter of an agricultural labourer (John Robertson) and she was the fifth child in a family of at least ten. The other daughters married labouring men and one of her brothers, Robert (the oldest boy) became a shepherd. But her three younger brothers ended up on very different paths. Walter became a school master, John became the Minister of the East Lothian parish of Whitsome and Alexander studied medicine in Edinburgh.

Seventeen

Scottish researchers amongst you will be aware of the significance of the year 1855. This was the year in which (eighteen years later than in England and Wales) civil registration of births, marriages and deaths was introduced in Scotland. And in this first year of the civil system – and this year only – a remarkable amount of additional information was recorded on the new birth, marriage and death certificates.

For example, in addition to the usual name, date and place of birth and parentage, birth certificates recorded the age and birthplace of both parents, the date and place of the parents’ marriage, the number (and gender) of children previously born to that marriage and whether those children were living or dead.

So, when my 2x Great Grandmother, Bridget Flynn, went to register the birth of her daughter Susannah at the register office in Corstorphine on 30 July 1855, she told the registrar that she had married Susannah’s father, John, in Edinburgh in 1853 and that this was their second child, having previously had a boy, who was still living. She also stated that John was a 25-year old farm servant, born in County Roscommon and that she was 22 and had been born in County Leitrim. As the censuses simply state that they were born in Ireland, the information regarding their birthplaces was a vital discovery.

The effort of recording all of this additional information proved too much and it was abandoned the following year. The question regarding the parents’ marriage was reintroduced in 1860.

National Records of Scotland ref: Statutory Register of Births 1855 678/23

Sixteen

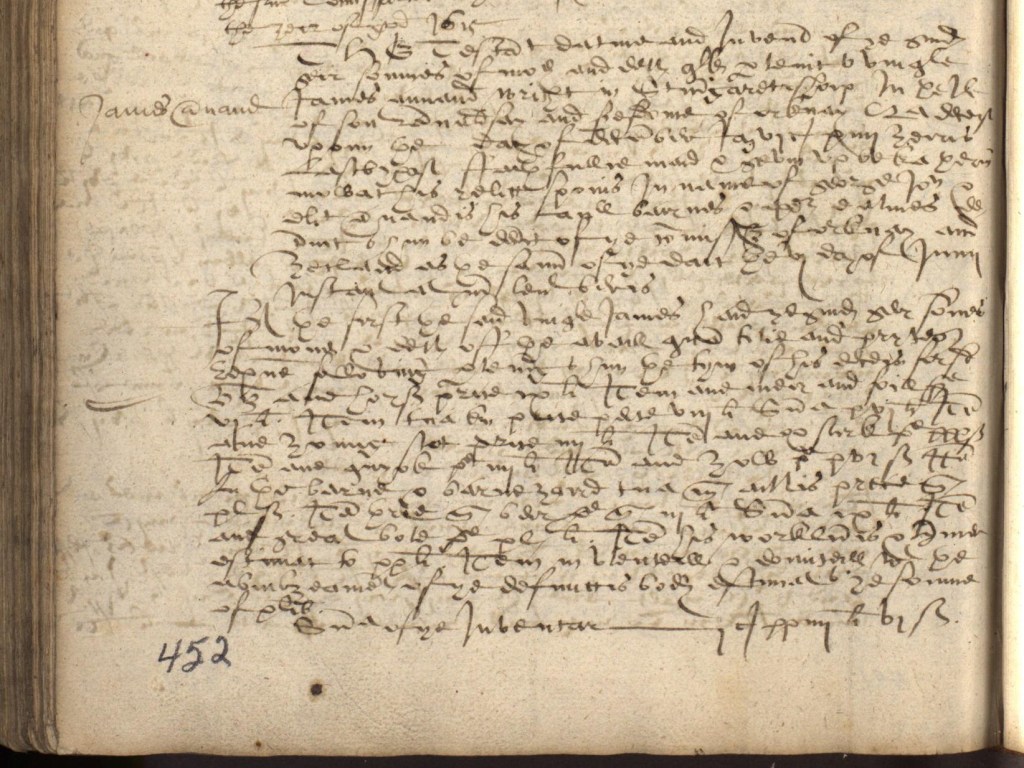

If my theory is correct, today’s discovery relates to my 9x Great Grandfather, James Annand. It’s a long story but briefly, the surname Annal appears to have evolved from the name Annan or Annand which is first recorded in Orkney in the late 16th century. The name Annand occurs in South Ronaldsay in the 17th and early 18th century but then disappears – at exactly the same time that the name Annal first appears. There’s convincing evidence that the names are one and the same.

This is part of the will of James Annand a ‘wricht’ (i.e. a wright or carpenter) of St Margaret’s Hope, South Ronaldsay who died sometime around 1615.

Fifteen

Family historians can be divided into two groups; those who are fortunate enough to have ancestors from the Isle of Man … and everyone else!

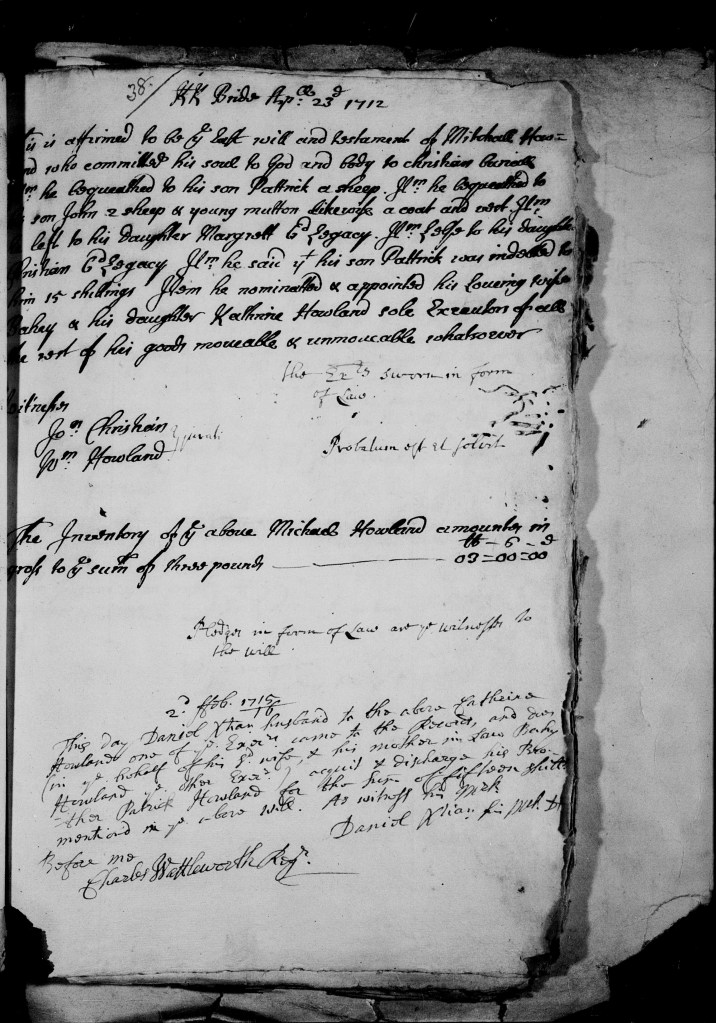

The records available to Manx researchers are simply stunning with the best set of land ownership/transfer records I have ever come across; virtually every Manx adult left some sort of testament and women routinely used their birth surnames in most legal records. A few years ago, I discovered the will of my 8x Great Grandfather, Mitchell (or Michael) Howland (c.1630-1712) who made bequests to his two sons and two daughters. We also learn that his daughter Catherine had married Daniel Christian.

If you have any say in the matter, I would strongly recommend that you have Manx ancestry!

Fourteen

This isn’t the first time that I’ve mentioned the Port family in this series of microblogs, and it won’t be the last. I knew nothing about them (I hadn’t even heard the name) when I set out on researching my ancestry over 40 years ago but they’ve become one of my favourite ancestral branches – certainly one of the most rewarding.

I remember looking them up in a published volume of the 1665 Oxfordshire Hearth Tax many years ago and discovering to my surprise that my 8x Great Grandfather, Richard Port was paying tax on more hearths than any other inhabitant of Dorchester, including the Lord of the Manor! I then discovered the reason for this; he owned one of the town’s many pubs. I believe that the family were running what’s now known as the George Hotel and although this isn’t actually specified on any document that I’ve seen (so far!) there’s some pretty good evidence in the shape of a late 17th century inventory.

The inventory of ‘all the Goodes, Cattles and Chattles of Richard Port of Dorchester in the County of Oxon. Innholder’ was taken on 9 April 1674 and is a mine of information. It lists Richard’s personal possessions room-by-room, including ‘the Chamber where he died’, ‘the Chamber over the Buttery’, ‘the Chamber over the Milkhouse’, ‘the Chamber called Gibbs his Chamber’, ‘the Swan Chamber’, ‘the Star Chamber’ and ‘the Chamber over the Woodhouse’. It’s unlikely that any other Dorchester inn would have had quite as much accomodation.

Oxfordshire History Centre reference: Pec.70/4/37

Thirteen

There’s probably nowhere on earth where my roots lie deeper than the Orkney island parish of South Ronaldsay. My Annal, Christie, Cromarty, Laughton, Scott, Berston and Groundwater ancestors all have their origins on this southernmost island of the Orkney archipelago. One of the most useful sources we have for researching South Ronaldsay is the 1821 census, recording the names of the 2231 inhabitants of South Ronaldsay itself and the neighbouring islands of Burray, Swona and the Pentland Skerries.

It’s a truly remarkable document which I’ve written about at length and there’s an enormous amount of potential for deeper research in its 65 manuscript pages. One fascinating fact that jumps out at us from the summary totals written on the last page is that the population comprised 1193 females yet only 1083 males; 53% against 47%. And much of that discrepancy is to be found amongst the population of young men. Of those aged between 16 and 25, just 43% are male.

A bit of local and social history quickly reveals the answer. It was quite normal for young Orcadian men (and this seems to have been particularly the case in South Ronaldsay) to spend some time working in North America (in the “Nor’ West”, now part of Canada) for the Hudson’s Bay Company. My 3x Great Grandfather, Peter Annal signed up for a five year term on 15 June 1820 (he’s not in the 1821 South Ronaldsay census) and later extended his stay in the Nor’ West by another five years before returning to Orkney in 1830. Today’s discovery is the copy of Peter’s 1820 contract, countersigned by his brother John and by John Rae, the father of the great explorer.

Archives of Manitoba reference A.32/20 f.319

Twelve

Other than the occasional reference to ‘Sinclair’s Cottage’ and the more-impressive-sounding-than-it-actually-is ‘Reid’s Castle’ on Eday in Orkney (it’s a very traditional small Orcadian croft!) I think I can safely say that none of my ancestors have a place named after them. Fortunately, my wife’s family can offer an altogether more interesting discovery.

To quote from the Victoria County History of Stafford: Volume 7, Leek and the Moorlands pp.37-41:

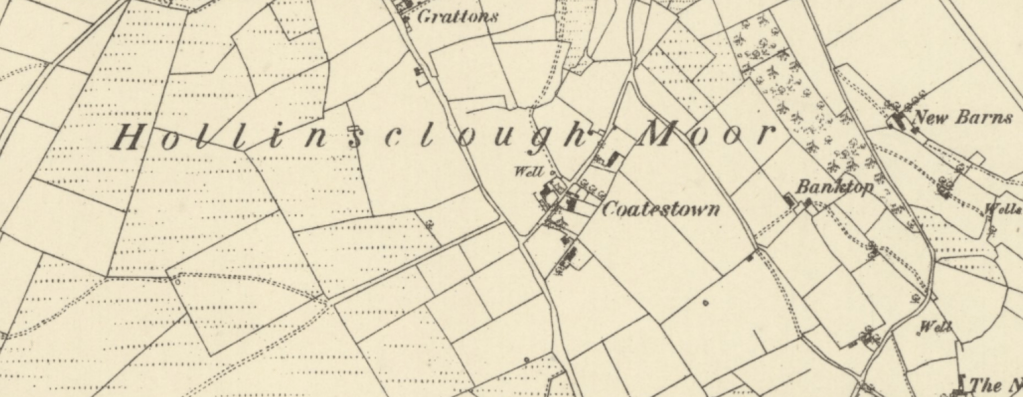

Houses on Hollinsclough moor include Coatestown, possibly the home of Isaac Coates, a chapman, in the later 18th century…

I can go further than this and say, ‘definitely the home of Isaac Coates…’ And Isaac Coates (1742-1787) was my wife’s 6x Great Grandfather. Not a bad claim to fame…

National Library of Scotland

Eleven

My English ancestry comes from one source; my great grandfather, Frederick Port, who left England to settle in Edinburgh in the 1880s, working for Cadbury’s. I’ve traced various branches of his ancestry and two lines in particular have led me back to stunningly beautiful English villages. The Port family itself came from Dorchester, Oxfordshire (the setting for Midsomer Murders) while another branch, the Trumans, hailed from the picturebook village of Lacock in Wiltshire.

The Trumans were butchers and some of them are recorded as supplying meat to the Talbot family of Lacock Abbey. I visited Lacock a couple of years ago and I was delighted to discover two substantial chest tombs, standing next to each other in the churchyard, both relating to the Truman family. They’re not direct ancestors but nevertheless, the two tombs are probably the grandest monuments I’ve found to any of my relatives.

Author’s photograph © 2022

Ten

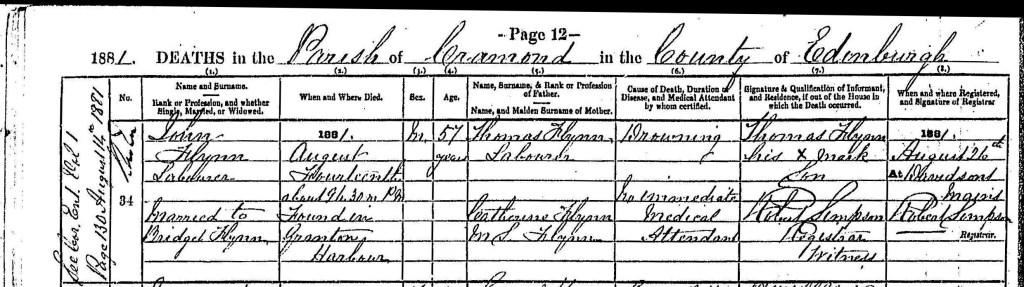

On 14 August 1881, the body of a 57-year old man was found in Granton Harbour to the north of Edinburgh. The man in question was my 2x Great Grandfather, John Flynn. On his death certificate, the cause of death is recorded simply as ‘Drowning’. There’s no clue as to whether John fell, jumped or was pushed, no suggestion that he was drunk or otherwise incapacitated, no comment about his state of mind. Even after the results of a precognition were received three weeks later, we just get that single word: ‘Drowning’.

The only clue I have, and it’s a slight one, comes from a very brief piece that appeared in the Edinburgh Evening News in May the same year. John Flynn, a labourer residing at West Pilton Cottage, Cramond, was charged with ‘having stolen a dog belonging to William Sneddon, fishmonger, Clarence Street, Edinburgh, from off the public road near Granton Harbour’ on 21 April 1881. He was sentenced to 14 days’ imprisonment. This is probably the man who died a few months later. He definitely lived at West Pilton Cottage, but so did his son of the same name, my Great Grandfather, so it could have been either of them but I suspect that what we have here is two signs of someone (the same person) suffering from mental health issues.

National Records of Scotland, SR of Deaths, 1881, Cramond 679/34

Nine

Sometimes the smallest discoveries are the best. And it doesn’t get much smaller than today’s discovery…

On 14 May 1853, on what must have been an extremely slow news day, my wife’s 3x Great Grandfather, Richard Graveson of Helsfell Hall in the Westmorland parish of Strickland Kettle saw his name appear in the ‘Local Intelligence’ column of the Westmorland Gazette.

Richard’s claim to fame? His Black Spanish hen had ‘laid the extraordinary number of three eggs one day last week.’

British Library Newspapers

Eight

I haven’t had much opportunity to use the wonderful Old Bailey Online website in the course of my own family history research. In fact the only close relative I have (that I know of) who was involved in a case heard at the Old Bailey is my 3x Great Uncle, Thomas Port.

Thomas is one of my most fascinating relatives. He was born in London in 1791, went into business with a distant relative (the husband of a cousin), dissolved the partnership, ran a drapers/grocers shop in St Pancras, moved to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire and had three children with a woman called Lucy Lambert without ever marrying her. Curiously, and inexplicably, he appears in the 1841 census and on the roughly contemporary records of the Tithe Commission as Thomas Thomas!

In 1823, Thomas, describing himself as a cheesemonger, was the alleged victim of a theft. A man called Thomas Allen was accused of stealing 4lbs of bacon from Thomas Port’s St Pancras shop. Port apparently ‘saw the prisoner moving something off the counter’ and followed him out on to the street where he confronted Allen and subsequently found the bacon ‘down the area of the next house, on the spot where he stood’. Astonishingly, Allen was found not guilty!

Seven

I’ve recently returned from a fortnight’s holiday in Germany and we spent much of our time there following up various leads on my wife’s Jewish side of the family. The house that the family lived in the Marktstraße in Landau-in-der-Pfalz is still in the family today (despite an enforced hiatus in occupancy in the 1940s…). We know the building well and we’re intimately familiar with its former occupants, with photos, documents, oral history and even, following our most recent visit, underwear to help us tell the story.

My mother-in-law was personally acquainted with many of the building’s former occupants and knew the house and the town very well as a child and we thought that we knew most of the stories, so we were surprised to discover a couple of years ago that another branch of the family had lived just along the Marktstraße in an even more impressive and historical house. The Haus zum Maulbeerbaum is in the middle of a challenging and expensive restoration project and we were thrilled to be shown round it by the project director a few weeks ago. My wife and daughter were probably the first members of the family to walk through the front door for nearly 100 years.

Author’s photograph © 2024

Six

My mum’s Flynn ancestors arrived in Scotland from Ireland sometime in the late 1840s. My 2x Great Grandparents, John Flynn and Bridget Flynn (yep!) married in Edinburgh in 1853 but their first child, Thomas, was born later the same year in Gateshead. The family’s short stay in England left an intriguing record behind.

On 14 December 1853, young Thomas was baptised at St Joseph’s Roman Catholic church in Gateshead; the parish register describes his parents as:

… Joanne Igo (prout sonat, communiter vero e matre nominatus Flinn) et Birgitta Igo vel Flinn nata quoque Flinn (minima vero ejusdem sanguinis) conjugibus hujus parocaio (ad tempus, nam maritus Edinam in Scotia, ubi uxor quoque mane[t] pergere statuit) et ex patria Connaughtiensi Roscommon et Leitrim

Which has been translated for me as:

[of] John Igo (as it sounds, but commonly known [from the mother?] as Flinn) and Bridget Igo or Flinn also born Flinn (but only distantly related) a married couple of this parish (for the time being, the husband lives in Edinburgh in Scotland, where the wife also intends to continue to dwell) and [natives of] Connaught – Roscommon and Leitrim…

So was my mum not a Flynn after all?

Tyne & Wear Archives ref: C.GA20/1/1

Five

When we attempt to retell our ancestors’ life stories we often find that there’s a gap of twenty to thirty years between the records of their birth and marriage – a period in which we know virtually nothing about them. We might assume that they attended some sort of school and that the males at least probably served an apprenticeship, but all-too-often, the details are lacking. Finding evidence that they did serve an apprenticeship can be a huge bonus and it can open up research possibilities in a number of other areas.

So, when I discovered that my 4x Great Grandfather, Samuel Port, had been apprenticed to his Great Uncle Jonathan Granger, a wealthy merchant in the City of London, my research horizons were instantly expanded. The indenture records all the basic details of the apprenticeship but crucially, it also tells me that Samuel’s father came from Sherburn (i.e. Shirburn) in Oxfordshire.

The London Archives reference COL/CHD/FR/2/1046/13

Four

The Scottish Old Parish Registers are a regular source of frustration – particularly when you’re used to the English ones which generally have much better coverage and which tend to begin much earlier. The OPRs can, however, be enormously informative. Take this entry relating to the baptism of my 5x Great Aunt, Rachel Philp in 1761. Her father, James Philp is described in the register as ‘Servant to Mr Keith of Ravelstone’. This is presumably Alexander Keith of Raveslton and Dunottar (1705-1792).

There’s nothing recorded about the Philp family’s residence at the baptisms of their six younger children but their youngest son was called Alexander and one of the witnesses at the baptism (in 1779) of the youngest daughter, Agnes, was… Alexander Keith! So it looks like there was a long standing connection with the Keith family. James Philp and the younger Alexander Keith (1736-1819) were the same age and probably knew each other well. It may be this Alexander who witnessed the 1779 baptism.

National Records of Scotland ref: OPR Births 678/20

Three

When it comes to projects like this and I talk about ‘my own family’, I naturally include my wife’s family. For a start it gives me access to some fascinating German case studies and it also provides me with plenty of English material, which is largely lacking in my mainly Scottish and Irish ancestry.

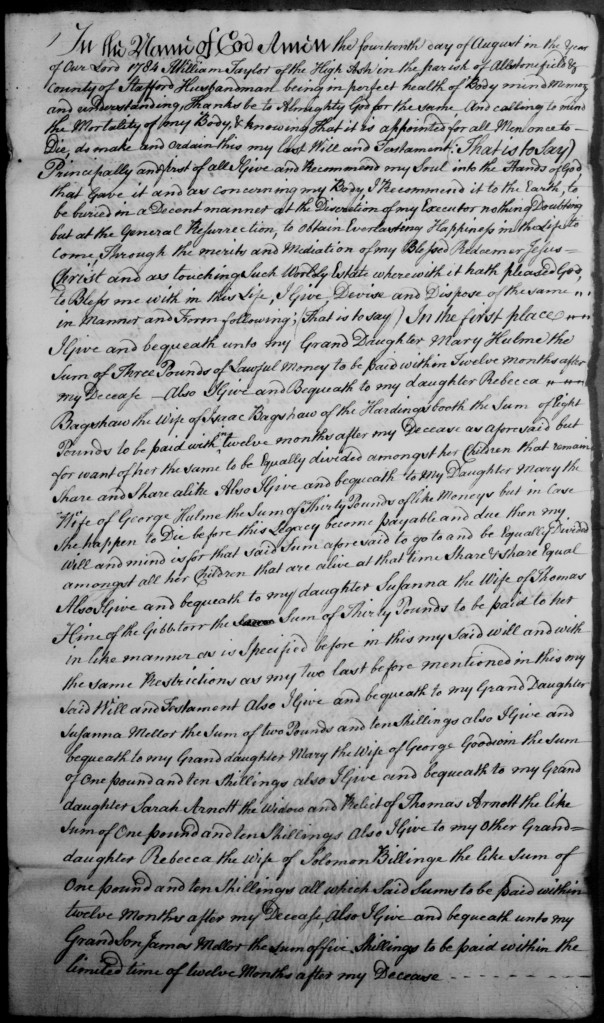

Today I’m looking at the will of my wife’s 7x Great Grandfather, William Taylor in which he names his daughter Mary and her husband, George Hulme (my wife’s 6x Great Grandparents). William had lived at the High Ash, a farm, high up in the Staffordshire moorland parish of Longnor, since his marriage sometime in the late 1710s. After William’s death in 1785, George and Mary took over the farm and it remained in the Hulme family until at least 1835.

Staffordshire Archives Service

Two

My 3x Great Grandfather, Robert Sinclair, is amongst my more prosperous Orkney ancestors. He ran a large farm in the parish of Orphir, just to the west of Kirkwall and I remember being disappointed not to have found a headstone for him in the churchyard at Orphir – he lived to the grand old age of 87 and died in 1910 – but I’ve learned over the years that family history research is very good at feeding you disappointments like this…

So, you can imagine my delight when, a few years ago, I discovered that he did have a headstone, but that he had been buried in the churchyard of St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall. The stone is still there today and holding up pretty well, with the famous Romanesque cathedral providing a stunning backdrop.

One

In family history research, the most interesting discoveries aren’t always the biggest ones. Ten years ago, while researching the life of my 2x Great Grandfather, Thomas Port, I came across a small notebook held by the Buckinghamshire Archives. The document is part of the collection of the Buckingham Congregational Church, later United Reformed Church, described in the archive’s catalogue as ‘Old Meeting Sabbath School minute book [Buckingham Congregational], 1842-1850’.

Mr Port is first mentioned in the minutes of the ‘Annual Meeting of the Teachers’ held on 13 January 1847 but he was probably a member before that. The minutes don’t tell me anything of huge genealogical significance about Thomas but they help me to picture him as an individual, and as one who held an important role in his (small) community.

Old Meeting Sabbath School minute book, Buckingham Congregational Church, 1842-1850

Buckinghamshire Archives ref: NC_4/1