The aim of this blog is to provide some background material relating to the issues raised in Episode 26 of my video series, Setting The Record Straight.

The video and this accompanying blog take a look at an online database that I’ve used a lot over the years but it’s only recently that I’ve discovered how really bad it is. I’m talking about the Westminster Rate Books database on Findmypast. The database itself dates back to the dim and distant days before Findmypast became Findmypast (who else remembers BrightSolid?) and unlike many of the databases that I’ve looked at previously, it’s not linked to digital images of the original documents. So, as far as online access is concerned, we are wholly reliant on the transcribed information.

Rate books and other similar records such as Land Tax registers, electoral rolls, directories, phone books, don’t generally, in themselves, provide us with a great deal of genealogical detail. Yet they are extremely useful sources for family historians for two main reasons. Firstly, when they’re indexed – particularly as part of a large database – they can help us to locate an ancestor in a particular place at a particular time. This can allow us to identify a potential place of origin for a ‘difficult’ ancestor.

Secondly, when we have access to a good run of records for the same place over a number of years, we can use them to look for changes – people appearing in the records (which might suggest a recent arrival in the area or that the person had recently qualified to be included – perhaps by becoming an adult or through inheritance of property) and people disappearing from the records (which might indicate that the person had left the area, that they had disposed of some qualifying property or, of course, that they had died). If we’re lucky the record might provide some additional clues to help us work out what’s going on.

City of Westminster Archives Centre reference: STP/H/2/H47 p.22-23

One of the most useful characteristics of these records – particularly records of taxation relating to land and property ownership – is that the compilers of the records, tended to enter the information in a logical order – essentially, the route over which the person who was responsible for collecting the tax would walk, door-to-door, street-by-street. And that order would usually stay the same year after year. So we can use contemporaneous maps to plot the routes that the tax collectors followed and this can allow us (sometimes!) to identify the actual properties in which our ancestors lived.

The Westminster Rate Books database is huge. According to the brief notes attached to the Findmypast database it includes ‘over ten million names of tax payers from the early seventeenth century to the end of the nineteenth century’. Rate books by their very nature give rise to vast databases – lots of names in annual lists over a long period of time – and in the case of Westminster, we’re actually dealing with a variety of different rates: the Poor Rate, the Pavement Rate, the Highway Rate and, my personal favourite, the Scavengers Rate – essentially, the equivalent of today’s waste collectors. And the records in the database include many which, strictly speaking, aren’t Rate Books at all – Overseers’ Account Books, Land Tax Registers and many more. Collectively, they comprise an exceptionally useful set of records and the fact that they have been indexed and made available online should mean that we have exceptional access to them. But, unfortunately, this is not the case.

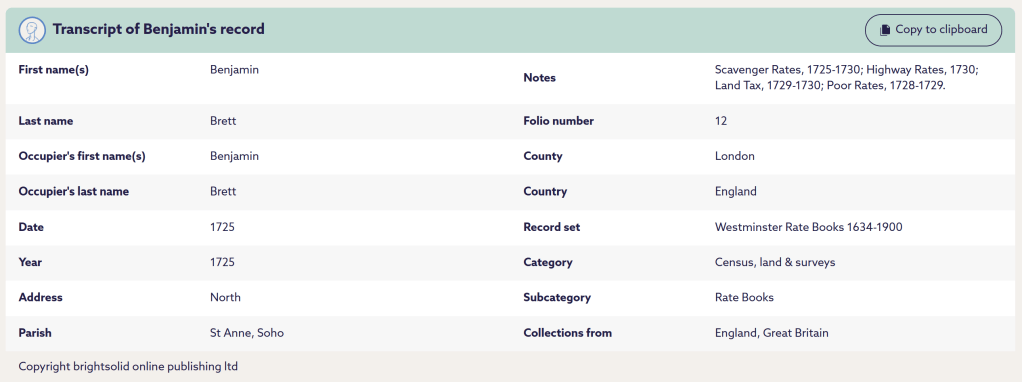

A few weeks ago, I was looking for someone who I knew to have been living in Westminster in the first half of the 18th century and I thought that he was likely to have been a rate payer. So I did a search in the Findmypast database, initially just entering his name – Benjamin Brett. And this is what I got…

My Benjamin had married in 1728 in the parish church of St James Piccadilly and was described in the parish register as ‘of St Ann’s Westminster’ so I was reasonably confident that this was my man. I was also interested to note that he was apparently in Soho, paying rates, three years before the date of his wedding, but also a bit surprised that there was no obvious record of him after 1725.

When I viewed the details I found that each of the four entries provided essentially the same information:

In fact, the only real difference (apart from a few minor differences in the spelling of Benjamin’s name) was that the third entry on the list recorded the ‘Folio number’ as 11 rather than 12.

But what was I actually looking at? What were these records telling me about Benjamin? Context is vital in all historical research and there was very little here. The ‘Address’ in all four records was given as ‘North’. Did this refer to a district in the parish of St Anne, Soho? Or was there a street called North Street? Without access to the documents themselves it was impossible to say.

And that’s when I discovered that the documents are available online – just not through Findmypast. I discovered that FamilySearch has a huge collection of records relating to Westminster and that they are freely available at home (not just at LDS Family History Centres). The challenge was to find a way of matching the unindexed records on FamilySearch to the indexed records on Findmypast.

It took me a while but I got there. And the key was the information recorded in the ‘Notes’ field of the results on Findmypast.

The FamilySearch website is a remarkable resource. Alongside the indexed records that many of us use regularly (parish registers, census returns etc.) there are thousands of collections of unindexed records. You can search the whole website by place and by keyword looking for potentially useful resources and in this case I was soon able to find a collection called England, Westminster rate books with covering dates of 1634-1900 – an exact match with the Findmypast database.

Scrolling down the list of ‘Microfilm Records in this Collection’ (don’t be fooled by the word ‘microfilm’ – what we’re dealing with here is ‘digital microfilm’) I quickly found what I was looking for: Public records of St. Anne’s Parish, Soho / St. Anne’s Parish (Soho, Westminster) and as soon as I saw the descriptions of the various ‘microfilms’ in the Note column, I knew that I’d found the link. The descriptions exactly matched the text in the ‘Notes’ field on the Findmypast results.

I was then able to browse through the relevant digital microfilm (Scavenger rates, 1725-1730; Highway rates, 1730; Land tax, 1729-1730; Poor rates, 1728-1729.) and what I found quickly gave me the answers to the questions I had about the results of my searches in the Findmypast database and equally quickly revealed the extent of the ineptitude involved in putting the database together.

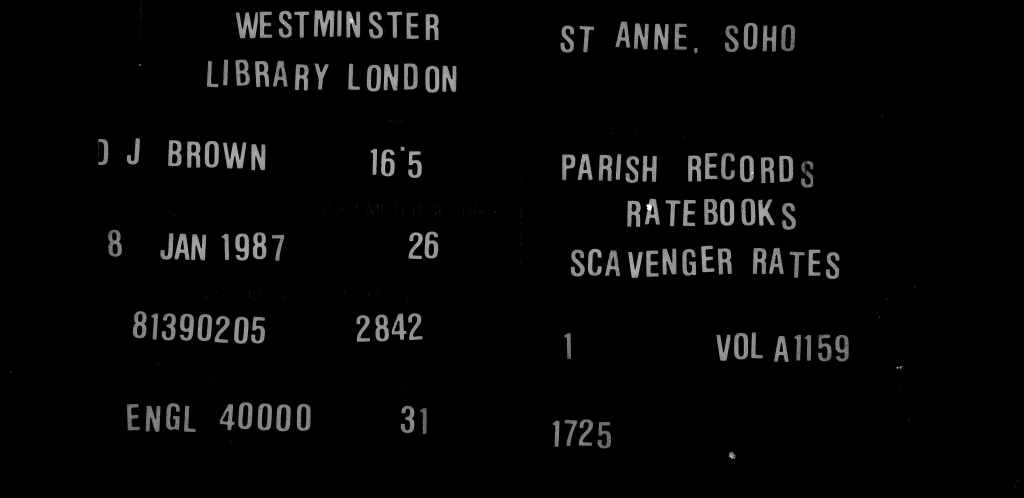

The records it seems had been microfilmed in 1987 and later digitised to produce the browsable digital microfilms – in this case, Family History Library Film Number 005109341, which comprises 1056 digital images. The ability to look at records in this way, by digitally turning the pages, allows us to understand the structure of a document and provides us with essential context. Each separate document is preceded by a ‘title page’ recording the high level information which, if the work had been done properly’ would form part of the data attached to the individual records contained in the document itself.

In this case, on the right-hand side we get the name of the parish, the description of the specific document, an archival reference, and the date (i.e. the year) of the specific document.

And after a bit of browsing I was able to find the four references to Benjamin Brett. And not one of them dated from 1725. I’ve put together a table showing the information recorded for one of the entries on Findmypast alongside the information that’s actually recorded in the documents:

Other than the parish name, there’s really not a lot to be said in defence of the Findmypast results. The year is wrong (it’s clear that what they’ve done is captured the first year of the description of the digital microfilm and applied it to every individual record) falsely suggesting in this case that Benjamin was paying rates in St Anne’ Soho in 1725. The address recorded – ‘North’ – is meaningless; you need to go back a few pages to find out that Benjamin was paying rates on a property on the north side of Compton Street. And we now know that what we’re dealing with here is a Poor Rate book. We also have the archival reference (A114) and we can find the document listed in the City of Westminster Archives’ catalogue and view it in its correct archival context:

It’s not the first example of Really Bad Digitsation that I’ve come across and I’m sure that it won’t be the last, but it’s certainly one of the worst. Not only does it not give us the information that we need (is it too much to ask for correct, full addresses and accurate document descriptions?) but it actually gives us wrong information – i.e. the year/date – which can easily lead to us reaching false conclusions about our ancestors’ lives.

I’m not sure that it’s fixable and it might be argued that it’s better than not having an index of these records at all. But I think that it definitely needs to come with some sort of health warning and I feel that the people responsible for creating the database should hang their heads in shame…

Copyright: David Annal, 21 November 2024

I so feel your pain and have run across instances like this as well…it’s so frustrating.

Sadly for me, the Rate Books images for St James Westminster available at FamilySearch start in the 19th century – I was hoping to see them for the 18th century to answer a tough genealogical question.

LikeLiked by 1 person