On 27 November 1826, the brothers, Robert, Walter, John and Alexander Robertson, presented an inventory of the personal estate of their father at the Edinburgh Sheriff Court. The brothers were described in the document as:

Robert Robertson Herd at Bronsley, Walter Robertson Schoolmaster at Cranshaws, John Robertson Preacher of the Gospel, and Alexander Robertson student of Medicine residing at Cranshaws.

National Records of Scotland SC70/1/35

Robert, Walter, John and Alexander were the brothers of my great, great, great grandmother, Elizabeth Robertson and to say that I was surprised to discover that she had siblings who were anything other than agricultural workers would be to considerably understate the case…

I’ve spent the last six weeks of my #365AncestralPlaces Twitter project exploring the houses, farms, churches, cemeteries and other places connected to my mum’s Border ancestors.

It’s a part of my family that I now realise I’d failed to pay enough attention to: my Berwickshire Davidson, Robertson, Gray and Liddle ancestors were mostly just names and dates on my family tree.

My virtual journey around my ancestors’ Borders homes has given me the opportunity to discover more about the people behind the names and the process of following them from place to place through the Berwickshire countryside (along with the occasional foray into the neighbouring county of East Lothian) has helped me to understand something about their lives.

Berwickshire was (and indeed still is) a largely rural county, dominated by agriculture and, in the 19th century, famed for its pioneering, innovative farming practices. Robert Kerr, a farmer from the parish of Ayton, wrote about the ‘recent and improved system’ which had ‘been adopted in this district’ and the ‘excellent system of husbandry’ which was ‘followed with skill and success’ (Kerr, Robert, 1809, pp.v-vi).

My ancestors earned their livings, almost exclusively, working on the land. They appear in the documents as ploughmen, hedgers, dairy maids, shepherds and hinds with the occasional one or two rising to the ‘rank’ of farm steward or grieve. I’ve been learning about the responsibilities attached to each of these roles from a book written by another Berwickshire famer, Henry Stephens (1795-1875). The Book of the Farm, first published in 1841, is considered to be one of the most important studies of mid-19th century agriculture, and was regarded by many as the ‘bible’ of farming, right up until the Edwardian period (Stephens, Henry, 1841). Stephens developed an interest in the finer points of farming while working on a Berwickshire farm in the 1830s so his writings have a direct relevance to my research, providing me with some excellent background material.

I don’t know how long my ancestors had lived in this beautiful part of the country but I was sure of one thing: that generation after generation of them had worked on Berwickshire farms and that while they were not by any means the poorest of the poor, they were, to a man and woman, solidly working class. And that was my belief right up until the point that I made an unexpected discovery…

John Robertson and Margaret Edington (or Idington) were married in the Berwickshire parish of Westruther on 29 November 1788. John and Margaret went on to have at least ten children; six girls and four boys that I know of, born between 1789 and 1806. The three oldest (Alison, Margaret and Mary) were born while John was a tenant farmer at Wedderlie in Westruther. By 1794, John had moved to take up the tenancy of the wonderfully named farm of Horseupcleugh in the neighbouring parish of Longformacus. Another seven children were born there (Robert, Elizabeth, Walter, John, Janet, Thomeson and Alexander).

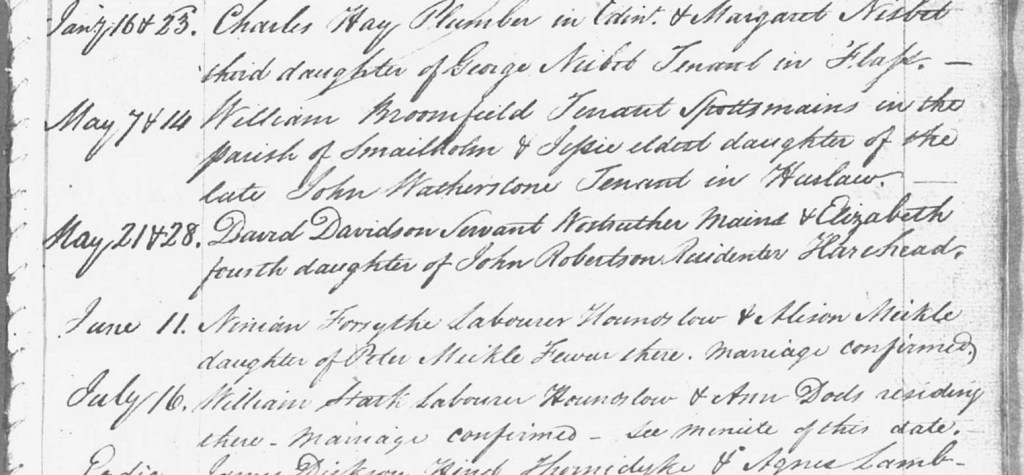

Elizabeth (born 1796) was my direct ancestor. In 1820, she married David Davidson, a man described on a variety of documents as an agricultural labourer, a ploughman and a farm steward and someone who exactly fits the expected profile of my Berwickshire ancestors. And when I looked at the marriages of Elizabeth’s sisters I found much the same.

National Library of Scotland OPR 756/2 p.105

The oldest daughter, Alison, married a shepherd, Margaret’s husband was described as a farmer on her death certificate (whether he was actually a farmer or a farm worker is hard to say), Mary married a farm steward and Janet’s husband was a carter. Only the youngest daughter, Thomeson, bucked the trend slightly by marrying a clerk and moving to Glasgow.

And the oldest son also fits the family profile: Robert Robertson (born 1794) worked variously as a letter carrier, a carter and a shepherd. So seven of the ten were involved in precisely the sort of work you would expect the children of a Berwickshire tenant hill farmer to be involved in. So it would surprise you (and it certainly surprised me!) to discover that the three other sons appear to have gone to university and ended up with what you might call professional occupations.

Sometime before 1826, the second son, Walter (born 1798), was appointed Parochial Schoolmaster at Cranshaws and in 1832, when a new school was opened in the parish of Whittinghame, he took up the same post there, a role he continued in until his retirement in the 1870s. I’m not sure whether Parochial Schoolmasters were usually university educated or not. Under the terms of the Parochial Schools (Scotland) Act of 1803, Section 16, the person elected to the role was to be examined by the presbytery who would:

“…take trial of his sufficiency for the office, in respect of his morality and religion, and of such branches of literature as by the majority of heritors and minister shall be deemed most necessary and important for the parish, by examination of the presentee, by certificates and recommendations in his favour, by their own personal inquiry or otherwise…”

But whether Walter went to university or not, it’s clear that he must have been a well-educated and well-respected man, in order to perform the role of Parochial Schoolmaster for around 50 years.

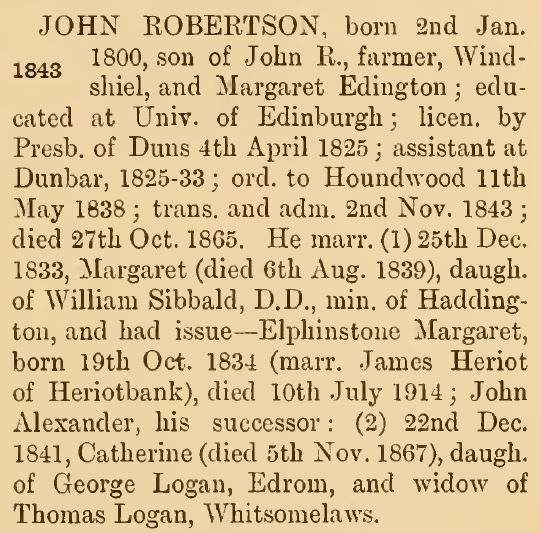

The next son, John (born 1800), was certainly a university graduate. According to the Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae (Scott, Hew, 1917), he was educated at the University of Edinburgh and, on 4 August 1825, was licensed by the Presbytery of Duns and took up the role of Assistant to the Minister at Dunbar. On 11 May 1838, he was ordained as Minister at Houndwood, moving to Whitsome on 2 November 1843. His first wife, Margaret Sibbald, was the daughter of Rev. William Sibbald the Minister of Haddington and their son, John Alexander Robertson (1836-1918) succeeded John as Minister of Whitsome.

And then there’s the fourth son, Alexander (born 1806) who, in 1826 was described as a student of medicine. Ten years later, on 9 June 1836, Alexander Robertson, ‘Surgeon, in this Parish’ married Jean Gowans in the East Lothian parish of Yester. Jean was the daughter of John Gowans, who farmed 158 acres at Carlaverock Farm in Tranent. Alexander and Jean had three daughters, the youngest born on 1 September 1840, by which time her father was dead. I haven’t yet found a record of the death of my 4x great uncle, Alexander Robertson M.D. but he must have died sometime in 1840. His widow never remarried; she survived him by fifty years, eventually dying in Edinburgh in 1890.

I am at a loss to understand exactly what was happening here. Why would one son end up as a shepherd, all six daughters marry into agricultural families (or similar) and yet the three youngest sons end up in academic professions? Why (how?) did John find himself as a student at Edinburgh University in the late 1810s/early 1820s? How did Walter get sufficient education to allow him to establish himself as a Parochial Schoolmaster? And I want to know more about Alexander – when did he graduate (from Edinburgh University?) to become Dr. Alexander Robertson?

Sometime between Alexander’s birth on 15 November 1806 and his father’s death on 8 June 1820, the Robertson family had moved from the farm at Horseupcleugh to yet another Berwickshire hill farm, at Winshiel in the parish of Duns and, six years later, his four sons were attempting to sort out his estate. (It’s worth noting here that while the total value of his estate was given as £158 15s 6d, all but £20 of it was made up of two debts owing to John since the year 1813, together with the interest on the same.)

It was the document confirming John’s sons as his executors preserved amongst the records of Edinburgh’s Sheriff Court that allowed me to make this fascinating discovery, opening up several new strands of research to me. As always, there’s still a lot more to discover…

Bibliography

Kerr, Robert. 1808. General View of Agriculture of the County of Berwick. London, Richard Phillips

Scott, Hew. 1917. Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae Vol. II, p.65. Edinburgh, Oliver & Boyd.

Stephens, Henry, 1841. The Book of the Farm. Edinburgh & London, William Blackwood & Sons.

© David Annal, Lifelines Research, 24 October 2022 (updated 27 November 2024)

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree